From the Bob Willard Collection, Volume 5

September 28, 2020

Bill Frisell walked down the even-numbered side of Cook Street from 8th Avenue toward 9th Avenue. He was 5′ 10″, brown from the sun, and full of anticipation. He approached 834 Cook Street, his home for thirteen years before his family moved a block and a half south to the upper-crust 7th Avenue Parkway. That move took place just last year. They still were living on Cook Street. Now in a Mansion on a Corner.

7th Avenue Parkway is one of the most cherished streets in all of East Denver. One mansion after another populate both sides of the parkway. Some have customized black iron fences and long driveways. Some perch on hills. Most have flagstone walkways, and they all seem to share the luxury of enormously large porches.

The parkway is professionally maintained and manicured. It is sprinkled with sugar pines and flower beds that are enclosed and protected by colorful blooming low-height bushes. You had to have done something financially substantial to live on 7th Avenue Parkway.

As he walked by his old house, Frisell passed 836 and 844 and 852 and 858 Cook Street. Once he was almost at the end of his old block, nearing the corner in front of the Collins’ house at 866, I abandoned the inside corner window of my house and walked out the front door. My house was on the diagonal corner. Address? 911 Cook Street. It was 7:55a when my front door clicked shut.

‘Hey Frisell, over here,’ I called out, waving my arms. Bill looked over, nodded and cut across the street.

The air was already morning crisp even though it was just the first week of September. The sun cast long shadows across the neighborhood.

‘You ready?’ I asked as we met at the bottom of the cement stairs; the last stair stamped with the ubiquitous oval Portland insignia.

‘Ya. I think I’m ready. Let’s go.’

And so Frisell and I began the journey of our first day of 10th grade. Our first day at East High School. It was quite exciting and nerve-racking. East High School is a gigantic school with 1000s of kids and a demographic breakdown of something like an even split: 50% white, 50% black.

As we left house after house behind us, we chatted.

Frisell: ‘Man, this feels weird. We’re not little kids anymore. High school here we come. Three more years. That’s like… forever.’

Sam: ‘I agree. At least we got out of junior high with no problem. I heard it’s dangerous being caught in the back halls of East by yourself.’

Frisell: ‘I heard that, too. It’s supposedly not too safe. Just stick with the crowds. And don’t act like Willard.’

Sam: ‘Always good advise, but he doesn’t mean anything.’

Frisell: ‘I know. He can’t help himself. I don’t really know what the ‘back halls’ is really even talking about. Do you?’

Sam: ‘Not really. That’s one of the first things on the list to find out about. After figuring out where our first classrooms are located.’

Frisell: ‘I doubt they have a sign up that says Back Halls. We’ll have to ask someone.’

Sam: ‘We’re supposed to go to the auditorium for an introduction to the school.’

Frisell: ‘Yeah. Probably some rules to go over. Did you get your locker number in the mail?’

Sam: ‘Yeah, my mom gave the letter to me. Mine’s on the second floor. # 2132. Maybe I’ll try to figure out where that is before my first class starts if there is time. How about you?’

Frisell: ‘Mine is on the third floor. # 3518. My first class in English on the third floor, so maybe my locker is close to that.’

The Portland cement stamp in the sidewalks was everywhere. You couldn’t go a block in Denver without seeing it ten times. It was everywhere on the walk to East. I assumed that Portland cement was made in Portland, Oregon. No one had said anything different. How was I supposed to know? Portland cement has nothing to do with Portland, Oregon.

It was founded in the early-1800s in England. Their original formula was patented in 1824. It’s had a dozen different formulas over the decades and has been used everywhere in the world for what is now more than two centuries. When you measure a business’s success in centuries, it’s probably worth investing in it. The name is ‘Portland’ because of the white stone originally quarried on the Isle of Portland in southwest England on the Atlantic Ocean.

Frisell and Sam continued to carve their way along the morning sidewalks of their neighborhood. Trees arching overhead from both sides of the streets cast shadows. Quite by accident, they ended up repeatedly stair-stepping one block down, then turned to walk one block over; another block down, then another block over; and so on, going north and then west with each iteration. This swallowed up more than half an hour, until the two of them paused at the end of Fillmore Street at busy, obnoxious, cacophonous Colfax Avenue.

Colfax Avenue is a five-lane jungle street well-known to residents of Denver. Two of the lanes travel east into the morning sun, two more lanes head west toward 14,265’ Mt. Evans in the Colorado Rockies front range. The center lane of Colfax Avenue is the suicide lane used for turning and swerving and confusion.

By and large, Colfax Avenue is an ugly commercial street that goes on for miles and miles. It’s one of the longest all-commercial streets in the US. It hosts a menagerie of businesses of common description: movie theaters, churches, bike shops, the State Capitol, average restaurants, below average restaurants, pizza restaurants, fast-food restaurants, coffee shops, bars, liquor stores, butcher shops, bakeries, flower marts, strip clubs, seedy vacant lots, burger joints, gas stations, lube and oil change locations, car washes, bail bondsmen, drug stores, donut shops, music stores, guys selling tamales out of meat wagons, adult book stores, pawn shops… most of it absolutely unequivocally, unremarkable. Few distinguished themselves. Other than the State Capitol, none make the guidebooks.

Except for East High School. It is a mighty structure with a long, distinguished, colorful history that shares a boundary with Colfax Avenue.

The 15th step of the State Capitol was marked ‘One Mile Above Sea Level’ from 1909 until 1969. Then, it was adjusted to the 18th step… and more recently, the 13th step. Someone is re-measuring. They keep getting more accurate readings or the building is sinking.

Along the dusty curbs on both sides of Colfax Avenue there is plenty of space to park a car. The asphalt and gray, concrete rectangles are likely to be cracked. Kool Menthol filter cigarette butts and Merit Regular cigarette butts coupled with crushed 3.2% Coors beer cans and broken glass from rum and whiskey bottles all lived together in clusters in the gutters. They were part of the Colfax Avenue panache. And part of the smell and the flavor and the grit.

Unlike visitors unfamiliar with choking, coughing, congested Colfax Avenue and its troublesome stop-and-go traffic, knowledgable neighborhood residents drove down serene tree-lined 13th Avenue or serene tree-lined 14th Avenue or beautiful tree-lined grand 17th Avenue, which partially caressed the southern boundary of Denver’s largest park, City Park.

Local residents avoided Colfax Avenue whenever possible, which was almost always. For example, to get to Karen Schoendaller’s house, the preferred route was to drive east along 17th Avenue to get to Jackson Street and then turn right, rather than ever travel east on Colfax Avenue to Jackson Street and then turn left. Lefts off of Colfax were difficult and sketchy.

Kathy Kissel lived just around the corner from Karen. She lived right on beautiful 17th Avenue between Garfield Street and Jackson Street. In elementary school Kathy Kissel earned the nickname ‘Kathy Kissel – the Flying Missile’. She reached extraordinary height in after-school gymnastics as Mr. Brown, every kid’s favorite gym teacher, would help launch her into the air following her running handsprings and backward flips.

Mr. Brown earned a deserved reputation as a life-saver after he rescued Terry Reagan from the cord of a tether ball wrapping around Terry’s pencil neck after a vicious pounding of the ball by humongous Latham.

Kathy Kissel’s house faced City Park. It was a lucky place to have your house in 1964 when a caravan of flashing-light, blaring-siren patrol cars ushered the Fab Four Beatles to Stapleton Airport, traveling along 17th Avenue right past Kathy’s house. They then turned left down Colorado Blvd to distant 32nd Avenue. The Fab Four had performed at Red Rocks Amphitheater that night. Had they travelled along Colfax Avenue, they may have missed their plane.

Nearing the airport, the train of celebrity transportation and professional protection flew by Oneida Street, just one half of a block from the one-story blonde house occupied by beautiful, high-profile, not-identical twins; Carol Cantrell and her surprise six-minute younger little sister, Cathy Cantrell. Carol and the Surprise were influential leaders and caring friends and kind classmates to many of us years later. Anyone that knew the Cantrell sisters was touched by them. Their reputations could not capture their immense positive influences and impacts.

Piano-teacher extraordinaire, Ann Pap, lived in a modest one-story red brick house directly across the street from Karen Schoendaller. Ray Gottesfeld took piano lessons from Ann Pap for many years. I took lessons from Ann Pap for one year, at my request in 10th grade.

Ray was both a very good accordion player and an accomplished piano soloist. I was neither. I was more of a clarinet kid along with Frisell. But Ray and I did have the same pediatrician, Dr. Max Ginsburg, who happened to be Frisell’s pediatrician, as well.

Dr. Ginsburg was one of my father’s closest friends. Two old-school doctors. The self respect was obvious. It was Dr. Ginsburg who examined me as an infant and told my father that he should go ahead with my adoption. That I would be fine. I owe it to Dr. Ginsburg that I was adopted by my parents. I owe it to my parents, too.

I hated getting annual shots in Dr. Ginsburg’s office but Ray was a champion shot recipient, dropping by for allergy shots as needed. Never putting them off. Ray didn’t give shots a second thought.

Dr. Ginsburg’s office had that horrible doctor’s office smell of formaldehyde or poison or whatever the heck it was which fills my nostrils in memory even now. R.I.P. Dr. Ginsburg. Great doctor. Great pediatrician. Terrible office smell. Shots to be avoided. Getting your finger pricked hurt like a mother f.

The Highlight magazines in Dr. Ginsburg’s waiting room were up to date. When I nervously thumbed through them I was okay with the Timbertoes and stalled at the Goofus and Gallant panels. I identified more with Goofus than Gallant.

I didn’t really act like Goofus but I found Gallant particularly bland and unappealing. He was Eddie Haskell polite but came with none of the good parts of Eddie. Gallant was a boot licking goody two-shoes. That wasn’t me at all.

Highlight magazine kind of forced you to identify with one or the other… and if asked, I knew that every single one of my childhood friend’s parents would place me solidly under the Goofus umbrella. That bugged me for the longest time. Truly did. But it’s true, and they weren’t wrong. There was little about me that was Gallant. Thank goodness. What a suck-up!

Here is a published analysis by someone who thought about Goofus vs Gallant too much:

When Goofus and Gallant began their broadly drawn moral plays, in the 1950s, they were depicted as identical twins. Later on, editors for Highlights indicated the two were brothers, but not twins. By 1995, they were simply two unrelated boys. But according to former coordinating editor, Rich Wallace, the two might actually be part of a Fight Club-style twist. “I’ve theorized they’re two sides of the same kid,” he said.

A lot of the kids growing up in our neighborhood reached fame, recognized for their accomplishments. Paul Huston, the tall classmate that grew up near Karen Schoendaller and Kathy Kissel, was a talented artist. He was hired in August 1975 to work as one of the very first artist/modelers for Industrial Light and Magic (ILM), the company founded by George Lucas. ILM is located in Marin County, across the Golden Gate Bridge, north of San Francisco.

Paul brought excitement to scenes in the original Star Wars movies. He designed and built the wings of the TIE fighters, the Death Star Cannon and the end portal of the trench that Luke Skywalker’s torpedo enters to blow up the Death Star. He created scenes in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Paul created a lot of visual effects for George Lucas movies; which means he created a lot of memorable big screen excitements that has brought joy to millions and millions.

Back in Denver walking with Frisell to East High School for our very first day of 10th grade, even at that somewhat early morning hour, traffic was choked on Colfax Avenue. Neither Frisell nor I were surprised that we couldn’t cross immediately. We would have been surprised if Colfax Avenue had not been impossibly crowded with traffic.

We stood and watched passengers in the front seats and the back seats craning their necks searching for street signs or addresses, slowing down in the middle of the block and then speeding up chaotically; sometimes pulling over to check maps that didn’t cooperate.

Occupants heading east into the sun had their visors down. Some wore sunglasses. It was a clear bright sunny morning. And it was 8:30a.

Time was still in our favor. We weren’t panicked but we waited anxiously for the lanes to clear and then ran across to the north side of the street at the first safe opening. We only had one more short block to go. It was 8:32a.

Continuing past the Red Barn hamburger joint, both of us silent and eager with forward looking stares, we traversed the final block to arrive at our destination, East High School. We entered its plum lavish grounds from the southeast Detroit Street corner. It was 8:35a.

Frisell: ‘There it is. Looks even bigger now that we’re students. Yikes!’

Sam: ‘Yeah, like a giant castle. Just needs a moat. I wonder if it has a dungeon.’

Frisell: ‘Doesn’t need one. It has the Back Halls, remember.’

Sam: ‘It’s not a joke.’

Frisell: ‘Yeah, I know. We both have lunch at the same time. Let’s meet up and see if we’ve learned anything about the Back Halls. If we’re both still alive.’

Sam: ‘Sounds good. I think they have pizza everyday at lunch as one of the choices. That would be cool. I hope it’s as good as the pizza at the Pizza Oven on Glencoe Street.’

Frisell: ‘Oh, man. That’s the best pizza in Denver.’

In front of the school building was a magnificent lush green lawn carpeting a gentle downhill slope which quickly rebounded ten feet away into a very slow rise. The grassy area was much larger than what had existed at Teller Elementary and at Gove Junior High. Both Teller and Gove could fit inside East High School two times each. They occupied much smaller footprints.

The lush grass at East High School had been freshly mowed and meticulously manicured. Incredibly, there wasn’t any visible clover and it was devoid of any fallen leaves… just lush green grass. Mature poplar trees in all directions framed the verdant scene which was alive and bejeweled by a kaleidoscope of fluttering butterflies. And iridescent blue darting dragonflies. Both in abundance.

It felt like arriving at a brilliantly verdant Oz. In the center of the picture rose the massive, awe-inspiring, four and a half story red brick, multiple-buttressed school building including its 162’ tall, four-sided clock-tower. Students buzzed across the grass and headed toward the entrance facing us. It was Tuesday, September 6, 1966. It was our first day in Grade 10. And in a couple minutes we were about to enter the south-side hallway of East High School for the first time as students. We made it in time. It was 8:40a.

One day before the start of the school year, Monday, the 5th, was Labor Day. The school years usually started the day after Labor Day. That year, 1966, was no different, although Labor Day was different. It was the first time that Jerry Lewis’ Muscular Dystrophy Association Labor Day telethon aired on teevee.

For 21 hours straight. Unanticipated at the time, we had to endure this Labor Day telethon burden for the next 43 years. Its last broadcast was in 2009. Jerry Lewis performed Jerry-schtick for 20+ hours each Labor Day until he looked exhausted, acted exhausted, and made all his TV viewers feel exhausted.

Each of those 43 additional years, the show went on for what seemed like forever. Every viewer got more and more exhausted. It felt like a suffocating shrink-wrap. I unabashedly admit that I stopped watching after year three but I heard it was continually exhausting. Never changed.

During the telethon, Jerry had fancy spokespeople and fancy performers and there was always Jerry and he had dancers and promoters and singers and kids with Muscular Dystrophy that Jerry loved to peacock on-stage and even more kids that Jerry loved were there and Jerry always wore a black tuxedo but for most of the time that he was on-air he didn’t wear a tie. He started the show wearing a tie and took it off sometime mid-airing to emphasize how exhausted he’d made us all feel. But we were doing it for a worthy cause.

The Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association Labor Day telethon wasn’t even the first TV marathon. Milton Berle had hosted a Memorial Cancer Fund marathon in 1949. There weren’t many TV stations back then.

In 1946 only 45,000 homes in America had a TV. Three years later, 1949, that number had grown almost 100-fold with 4,200,000 homes heating up vacuum tubes to deliver TV programming, displayed on large, flickering cathode-ray tubes.

In 1953, one-half of the houses in America had a TV. Perhaps auditioning, Jerry Lewis and his famous singing partner, Dean Martin, performed on that first TV marathon hosted by Milton Berle.

Martin and Lewis were the #1 show business act in America. And that continued until they broke up in 1957. Their reunion, twenty years later, was one of the most-anticipated events in television history… and it occurred on the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association Labor Day telethon in 1977.

But I didn’t see any of that marathon. I was busy. I had something else to do. I have no idea what I had to do. I just say politely that I was busy. Just like what Gallant would say.

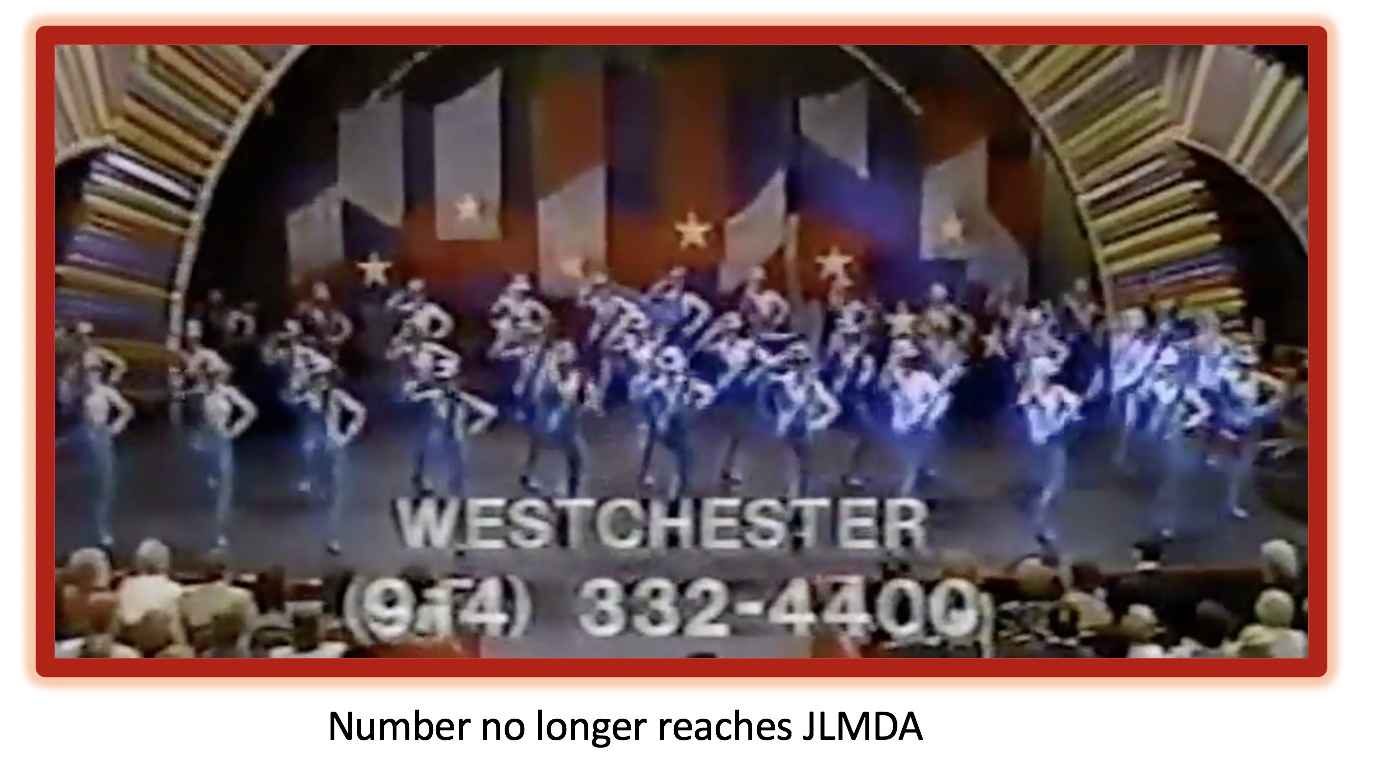

The JLMDALD telethon was the first television show I’d ever seen that stretched city names across the screen along with phone numbers for viewers from the city currently being shown to call to make a Muscular Dystrophy Association Jerry’s Kid donation. You saw it. You remember the American celebratory dancing girls kicking their legs far above their noses, forever in smile.

If you call the phone number on the screen above today (2025), the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association doesn’t answer. No forwarding phone number is provided. So save your dime, uh, I mean quarter, unless you’re looking for a victim’s law firm in Westchester. At least that’s what I think the guy said on the other end of the line after I patiently waited fifteen rings until he answered.

Had the gentleman scraped the peanut butter sandwich off the roof of his mouth prior to answering my call, I may have understood him better. To be fair, I did call during his lunch hour, unless his firm has strange lunch hours. It is also possible that the garbled verbal exchange between us was a collision of an excess of upper palette peanut butter in his mouth coupled with an over-accumulation of ear wax in my canal on my part. I don’t know. I didn’t ask myself. Or maybe I did but I couldn’t hear myself. I’m not good at remembering details like that.

Also coincident to our start of high school, Star Trek first aired on teevee the week that school started in September of 1966. It aired two days earlier in Canada than it aired in the United States. Two of its biggest stars, William Shatner (Captain Kirk) and James Doohan (Mr. Scott), were Canadians. Might have something to do with Star Trek being aired up in the frigid north first.

No longer Canadian residents, Shatner and Doohan would not have been required to include income earned outside of Canada when filing their Canadian tax returns. This saved them a lot of money.

Canada and the United States have different tax laws and they have different money. One sentence, two differences. ‘Loonies’ are what Canadians call their $1 coins (introduced in 1987). On the back of the brass ‘loonie’ is a loon… a medium-length neck, water bird.

Canadian legal tender also includes a $2 coin called a ‘toonie’ (introduced in 1996). It can also be spelled ‘twonie’ but the Royal Canadian Mint prefers it to be spelled ‘toonie’. As a nickname spelling you wouldn’t think they’d care but they do. They can be picky even when being polite about it.

Even more recently (2012) Canada ditched their worthless penny. There are no pennies being minted or exchanged as currency in Canada any longer. The cost of copper exceeded the value of the coin.

Sometimes Canada gets things right before the U.S. gets it right. The elimination of the penny is one example. The U.S. should eliminate pennies, too.

Additionally, since the $1 loonie and the $2 toonie are both coins, they last forever. Canadians save a lot of Canadian trees by not printing paper $1 bills or paper $2 bills that used to get dirty, tear, burn, wear out or fall out of pockets and silently hide in the bottom of hockey gear bags, never to be seen again. Disintegrating. Canadian hockey gear bags stink to high heaven and Canada is already closer to high heaven.

Another money example of Canada doing something right is that Canada no longer has $1 bills and they no longer have $2 bills. Plus, the bills that they do have — $5, $10 and $20 — can’t be torn. They are tear resistant. It means that Canada spends less time and less money making money. There is a fiscal printing saving. Do they burn? I haven’t checked.

The smallest Canadian bill is their blue five-dollar banknote. The outdoor scene on the back is of kids playing hockey on a frozen pond. By law, Canadians can’t go five minutes without thinking about hockey. Yet, they currently (2025) have not won the Stanley Cup trophy in more than 30 years. Canada’s Montreal Canadiens kissed the cup in 1993; no Canadian team has smooched it since.

I lived in Canada for 15 years making sports video games. You have to know something about sports to do it. First of all, you have to know the rules pretty good.

Then you discover that in one way or another every sport has a design flaw that is sometimes covered up by the rules. Whether it’s for how the game is played or how it translates to the sports fan.

Take for example, baseball.

Baseball has a major design flaw that didn’t get ‘corrected’ for nearly 40 years. A close semblance of baseball began being played in 1846. In 1895, the league slapped on a band-aid rule.

It had to do with a player in the infield who would purposefully miss a pop fly ball to throw out the lead runner without problem and increase the chances of turning a double play. It’s famously known as the Infield Fly Rule. The design issue occurs because baserunners can’t advance to the next base before the ball is either caught or missed (the baserunner has to ‘tag up’). By missing on purpose, the fielder has a big advantage to throw out the lead runner. And then the ball to first base for a double play.

To make a basketball video game, you need to know all the rules including when the trade deadline occurs in the NBA and implement that into the design. In the 1990s, the NBA trade deadline was set at the 14th Thursday of the season… but almost no one in the world knew that. They didn’t know how the date was derived.

Hockey has a different sort of flaw relative to baseball. It is an ‘observation flaw’. It’s a flaw for the fans in the stands and at home watching on teevee. Whenever I raised it as such in Canada, Canucks within ear shot typically choke on their maple scone. Or push their Tim Horton timbit doughnuts into the trash. Politely picking up whatever remnants may have missed the mark. My suggested solution was blasphemy to their ears and an insult to the nation.

I noticed that when watching hockey, the Canadian hockey fans excitedly react to goals. There is no anticipation or expectation of goals being scored. Even on power plays, goals are only scored on average around 20% of the time. Yes, a team might get hot and increase their power play goals to 30% for a brief stretch. But still not enough to make a fan expect a goal. They are hopeful with no honest expectation. Even so, when asked, most Canadians say power play goals occur about 40% of the time.

In addition, I also noticed that the Canadian hockey fans don’t seem to really care when penalties are called during a game. They are excited that there will be an ensuing power play… but as stated, those don’t translate to goals being score at a high enough occurrence to rise to the level of expectation. Expectations in sports can be met or fall short.

The rules of hockey are missing an opportunity.

To fix this, my proposal is for each team to have a limit on the number of penalty minutes per game… say 12 penalty minutes. If a team reaches this limit of penalty minutes, a one-on-one ensues for every penalty thereafter between the goalie for the team with the infraction and an opponent handling the puck. This creates a valid expectation of a goal being scored. Fans would then care when there is a penalty called against their team because it reduces the number of penalty minutes their team has left before triggering the one-on-one. And if the other team is the one that has a penalty called on them, the fans are excited because their team is closer to the one-on-one in their favor.

Years earlier than any of the aforementioned, as a Boy Scout, an upstanding member of the Flaming Arrows Patrol, I endeavored, endured, and eventually earned a Cooking Merit Badge. I had wished and would have preferred to have been in the Snake Patrol, because the Flaming Arrows Patrol uniform patch looked like cack, which I think is Flemish for shite; derived from ‘kakken’ as in, “I was so scared, I nearly dropped a ‘kakken’ into my underpants”.

The Cooking Merit Badge was just one of four merit badges that I loaded up on during my two-year tenure as a Boy Scout. I had already earned the Swimming Merit Badge, the Soil Conservation Merit Badge, and the Lifesaving Merit Badge… but this time, it was the Cooking Merit Badge. Frankly, adverb of frank, it wasn’t that difficult.

Basically, all you had to do was fry up some bacon and eggs, feed them to the Scout Master, now ‘Scout Counselor’, probably soon to be called the ‘Scout Therapist’. If the Scout Master doesn’t throw up the bacon and eggs… you earn the badge.

You don’t walk home with the merit badge that day. It’s presented to you at a big ceremony where they announce your name, and as you rise up from your metal chair in the audience to applause, and shuffle and squeeze your way through a long row of knees and more metal chairs, you go up in front of everyone amidst the blaring cheers and the celebratory whistles, and the Scout Master presents you with the small, unimpressive 2.0 inch diameter circular patch that you stuff into your pants pocket to bring home to hand to your mother so she can sew it on straight onto your army green Boy Scout uniform’s upper cross-body sash. (Sashes are never to be worn over the belt; an emphatic rule even in new Boy Scout manuals.)

The culinary occasion I had selected to highlight my cooking skills was scheduled in the morning following an overnight camping trip. The location happened to be beside a river in the mountains. There was a sticky yellowish sap present on some of the trunks of the trees and a small field of yellow yarrow growing next to tall grasses and dirt paths with circular campfire pits punctuated here and there.

Also in view were an array of tents in differing states of erection. Many remained flat with center poles lying at the sides with short lengths of rope in the dirt. Many younger scouts had not yet demonstrated a ‘pitched tent’, as they say. At one point, there was a snake shivering along the ground beside the river. Willard rushed to see it and was waving it around like a lasso five seconds later.

Once I finally got my fire dancing, aided by a squirt or two of Kingsford lighter fluid sparked by waterproof matches, and once I had somewhat made my Scout’s cooking-kit pan level so it wouldn’t tip over and was heating confidently above the flames, I cooked the bacon and the eggs, and fed the culinary combo to the Scout Master.

He took a bite and apparently it didn’t taste like ‘kakken’ to him and all seemed good. I believed I saw a subtle wink and head nod from the Scout Master out of the right corner of my right eye. In all honesty, I had put my cooking-kit pan back on the flames while serving the Scout Master, and had, distracted, seriously over-cooked the remainder of my huevos and bacon concoction. There became a considerable buildup of steaming black crust cementing to the inside of my official Boy Scout cooking-kit. It was at that moment that I fully understood the term ‘mess-kit’. I never fully grasped the meaning of the term before that moment.

The big Merit Badge award celebration and ceremony was held a month later at the Capitol Heights Presbyterian Church on the corner of 11th Avenue and Fillmore Street. The big Boy Scout ceremonies were always in the basement at that church. There was a large room with a medium-height ceiling and a kitchen down there. The entrance available to us was from the alley, with a surprisingly narrow single metal door. Inside was a big crowd with lots of scouts and parents and scout leaders, and commotion and excitement, and conversation. They even served coffee and finger desserts on a side table.

My dad didn’t attend these sorts of things that often; but this was one of the very few times that it ever happened. In fact, I remember only one other such ‘event’, that my father attended which happened to be a Father-Son Night at Teller Elementary. He went to that, one time, and I remember we were one of the first ones to drive back home after eating campfire hamburgers. There were some policemen there that night that were going to show off their police dogs but we didn’t stay for that part.

My father was older than the other kid’s dads, and that was fine with me but it didn’t go without notice. He had a perpetual bad back that sequestered him to lie on the couch after dinner to watch teehee – Perry Mason being a favorite. I did, however, play Scrabble against him about 55,000 times at our dining room table while growing up. I got pretty good at playing scrabble and even today no one ever wants to play against me because they know they will lose. And I know they will lose, too. And that’s what annoys them the most; they know that I know that they can’t win. It was really a rare occurrence for my dad to attend any type of event with me like the Boy Scout Merit Badge ceremony. I think my mom talked him into going. I don’t recall my mom ever being able to talk my dad into going to anything like it, again.

So, my dad and I were seated next to each other in the audience at the Boy Scout Merit Badge ceremony. After singing God Bless America with a scout presenting the American flag, a few announcements were made about upcoming overnight trips and they asked for a show of hands from the scouts as to how many of them would be interested in a two-night overnight, riding horses into the mountains (ugh – horses scared the kakken-less out of me).

Then, finally, deserving scouts began to receive their merit badges. Tim Crow gets called up and is given his Cooking Merit Badge while everyone in the audience respectfully claps and cheers, and he shakes the Scout Master’s hand and returns to his seat next to his mother, Lucille Crow.

Then Steve Irwin gets called up to get whatever badge he’d earned, and then Miles Kubly, and they’re going alphabetically by last name. Alan Burnett didn’t get anything that time cuz he would have been called up first, but he wasn’t called up, and neither his mother nor father were there. The scouts that had last names that started with an ‘L’ and ‘M’ were called up, and finally they arrived at scouts whose last names started with ‘N’. They called my name: ‘Flaming Arrow Patrol Boy Scout, Sam Nelson, from Troop 1’ followed by a lot of hooting and hollering from my friends. I think I detected a small smile from my dad, which lightened my step. I was proud to have my father at the ceremony.

I hadn’t read all the Boy Scout of America Cooking Merit Badge instructions. I glanced at them. Okay? Actually, I read the first two or three bullet point paragraphs to get the gist of the requirements. I identified what minimal thing I had to do, and then I ‘glanced’. I don’t recall doing a full ‘skim’ of the instructions. It was a ‘glance’. But I didn’t ‘ignore’ the instructions. I ‘glanced’.

Someone, I don’t think it was Willard as he wouldn’t hang me out to dry, had dug up my official Boy Scout of America blackened cooking-kit pan assembly, the one that I had thrown away after burning it up to a black crisp and hidden it in the muddy riverbank. The Scout Master didn’t present me with my Boy Scout of America Cooking Merit Badge, but rather, reached down at the podium and presented me with my dug up, cold, greasy, dirty official Boy Scouts of America cooking-kit pan assembly, along with my Scout-issue metal fork with bent tines, and told me that after I clean it all up to a mirror-shine, I would then officially complete the requirements to earn the Cooking Merit Badge.

Occasionally, I have had an ability to really make an audience laugh, and this was one of those times. Everyone was laughing except for two people: and the one that wasn’t my father was me.

Waiting for our turn to enter the south door, Frisell and I walked into East High School for the first time as students. The hallways seemed as wide as Colfax Avenue. They were lined with 7’ tall red school-color lockers with opened spin-dial number locks hanging down from them. Rather than being crowded with cars, the hallways were stampeded by students excitedly going a million different directions. It was like being in the middle of a high school beehive.

It was loud and there were a lot of smiles and hugging from classmates getting together again for the first time after summer vacation. Above the large clock hanging down from the ceiling in the front hallway was a big red and white banner that said, ‘Welcome: Class of 1969‘, and that made all of us feel pretty good. There was always something special about being the ‘Class of ’69‘ for reasons requiring no explanation, and it seemed to make bonding easy. Staring up from below the hanging clock was Charlie Wagner, another neighborhood friend, and a member of our inner circle.

Charlie and I went way back together. We started a lawn mowing business together in the summer following 4th grade. That summer was one year prior to the summer that Frisell and I had held our one-day 25¢ Brownie Sale business. The lawn mowing business, however, lasted more than a day. I was always very meticulous about things, later called ‘anal’, and what nowadays would be called ‘obsessive-compulsive’. So was Charlie, so we did a great job on the lawns of our clients. Our rate was $5 for the job. Some clients would give each of us a $5 bill and that made us feel rich. The job we provided included mowing the lawn, front and back, and clipping along the flower beds and sidewalks, as well as bagging the remains and hauling them away. But we outperformed expectations and learned the value of that early on. It didn’t take long to feel as though we deserved the extra $5. If a client didn’t give us a tip, we tried to do a better job the following week. If we didn’t get a tip after a few times, we found other clients.

Charlie lived on 12th and Adams Street, three blocks from the Bluebird movie theater on Colfax Avenue. He and I suckled Saturday afternoon double headers together quite often. Lots of cowboy movies. I think we must have seen The Magnificent Seven fifty times, and of course, we knew all the lines. James Coburn’s knife throwing scene was the coolest thing we’d ever seen, but when he shot a bandito escaping on a horse from 200 yards away, having steadied a solid two-handed aim with his pistol, it was amazing to see the bandito drop from his horse two seconds later. When enthusiastically congratulated on the ridiculously impossible shot by the youngest member of the ‘Seven’, the kid, crying out, ‘That was the greatest shot I’ve ever seen in my life,’ Coburn turned and corrected, ‘The worst. I was aiming for the horse.’

So along with Frisell, Charlie Wagner and me, the new Class of ’69 crowded into the high school auditorium. Each of us was handed a card with a chant in red ink printed on it as we entered. Our school colors were red and white.

I waved to Gary Buckstein and other friends from Gove Jr. High that I saw. The cavernous auditorium had very high walls, three enormous sections of seats, lots of rows, and a big overhanging balcony. On the stage at the front was a line of cheerleaders dressed in red and white, of course, and a metal stand with a long-corded red Lollipop microphone at the top.

The atmosphere was very friendly and welcoming, and organized, and it took a while for the auditorium to fill up. I saw a lot of kids that I’d gone to school with scattered all over the auditorium. I waved and kids were shouting to one another from every direction. A girl a couple of rows ahead of us got up and waved to a friend of hers somewhere behind us.

High school was already an improvement over junior high. The majority of the kids in the auditorium were kids that I’d never seen before. I couldn’t stop looking at the new girl who was waving, whose name I didn’t know.

Once everyone settled into their seats as encouraged by the on-stage cheerleaders, our first official event at East High School began. There was no teacher, just the row of cheerleaders. One at a time, they walked to the center front of the stage, performed a cheerleader leg kick while shaking pom-poms, grabbed the red Lollipop microphone and announced their name, told us what grade they were in, and welcomed us to East High School.

Following proclamations about how great a year it was going to be for East High School, they asked us to read from the card we were given at the door. They led the printed cheer for the upcoming football game. It called out in rhyme for the defeat of the Loveland High School varsity football team on the upcoming Saturday afternoon, at 2:00p.

Each Friday afternoon following the last class of the day, the cheerleaders would host a short assembly in the auditorium, cheering on our football team for the next day’s game. All the varsity football games would be played at South High School’s football stadium. It was suggested that we each buy the $5 seasonal Athletic Card. It was required to get into the games. Tables would be set up in the front hall for the rest of the week. Our varsity football team had started practicing a few weeks before school started. But we hadn’t been in the school more than half an hour and were already excited and playing a part in the whole thing.

A teacher entered stage left and announced that a test was going to be passed out and we weren’t allowed to even look at it, much less begin taking it, until everyone had received one. Only then would he give us the go-ahead. He was a new English teacher to East High School. His name was Mr. Nelson.

The cheerleaders walked up and down the aisles handing out stacks of tests to the kids on the aisle seats and instructed them to pass them across. Frisell handed the stack to me, I took one, and passed the rest to Charlie, and he took his. There we were looking around looking at everyone else looking around, shaking their heads, in unified disbelief. The mood in the auditorium shifted to a lower gear due to the melancholy turn of events. They passed out a test?

‘I can’t believe it. Is this serious?’, I whispered to Charlie.

‘It must be some sort of a placement test,’ reasoned Charlie.

‘I hope not,’ interjected Frisell. Frisell had forgot to bring a pencil.

‘Here, take mine.’ I had an extra pencil.

‘Did you see that girl with long brunette hair a couple of rows up?’ asked Charlie.

‘Of course. I saw her in the side hallway, saw her in the front hallway, saw which door she entered, and watched her sit down. Why do you think I picked these seats?’ I explained.

Unknown to me or Frisell or Charlie at the time, the waving girl became Rebecca Gallegos. And she must have been noticed by a lot of students because she was voted the Angelus Queen at the first fall sophomore dance just six weeks later. We were the East High Angels and the yearbook was called the Angelus. Below is the picture from the yearbook of her eating cake at the dance after being crowned Angelus Queen.

But the hypnotism that was Rebecca Gallegos was interrupted brusquely. Into the red Lollypop and over the loudspeaker, Mr. Nelson took control:

‘This is a twenty-minute test. I will time it. Once I tell you to begin, open the booklet, sign your name on the top line, and good luck to all of you. Follow the instructions closely. You do not have to complete the entire test. You may now begin.’

And with that, Mr. Nelson clicked his track-team coach’s stopwatch.

The instructions were a couple of paragraphs explaining who developed the test, and that it was not a placement test. It would not impact or alter any student’s eligibility for any classes, so we did not have to worry about that. But, it continued, it’s still an important test and it described the test as having different kinds of sections, including multiple choice and problem solving. And it said to read through the entire test before completing anything it may ask of us.

So, along with the army of sophomores in the auditorium, I began reading the problems and questions from the beginning. There were a lot of very strange instructions in there, like:

12) ‘Moo’ out loud like a cow for five seconds

14) Stand up and scream your name out two times

And a lot of weird stuff like that. There were only three pages and I was anxious to get going, so I turned the pages to get a sense as to how much of this there was going to be to gauge whether twenty minutes would be enough time, or not enough time, for me to get through this.

As I rushed ahead analyzing the contents, some kids started mooing loudly while others were clucking like chickens. A girl was performing a chorus of Mary Had a Little Lamb pretty much on key. It didn’t take long before almost everyone was jumping up and down, or acting out being a horse or a donkey or some other barnyard animal, along with singing and stamping feet, and even a recital of the Pledge of Allegiance.

And there were a few kids not doing any of this, just remaining silent.

It was difficult enough to focus with that girl two rows up. It became evident to me once Frisell stood up and exclaimed, ‘Give me liberty or give me death’, that there were different variations of the test because my test didn’t include saying ‘Give me liberty or give me death’. I also wasn’t instructed to cluck like a chicken.

Then, Charlie stood up and started hee-hawing.

The girl who waved with the long brunette hair two rows in front of us hadn’t stood up. I was watching. She must have received one of the silent tests. Which wasn’t what I was hoping for.

And then I got it. The second to the last line of the test, couched at the bottom of the page, said: Re-read the entire test without doing any of it… REMAIN SILENT. The last line instructed me not to divulge to anyone sitting nearby to stay quiet. We are all in this game alone.

The kids in the auditorium remaining silent were the ones who had read the instructions to the end, the Readers… while the other kids screaming stuff out, hopping up and down like bunnies and running around the auditorium singing Born Free at the top of their lungs were the Skimmers. They were the kids that didn’t listen to the instruction, just glanced at the test, and didn’t read to the end. They were the kids that hadn’t yet been caught only doing 85% of the work to earn a Cooking Merit Badge.

In an ironic twist, the kids doing all the shouting and honky-tonking were momentary Goofus’s and I became a one-time Gallant. I couldn’t contain my smile as I sat listening, watching… and wishing my father was there. And wishing that the girl two rows up would get up and wave at her friend again.

At twenty minutes, everyone was instructed to stop the test.

Then, the purpose of the test was explained by Mr. Nelson that ‘following directions’ was important in school, as it would be in life. It wasn’t the first time I’d been taught that. He had told all of us to read to the end of the test before executing any of it… and about 90% of the class didn’t abide. It was a good lesson. Hour one. East High School.

The school bell rang announcing ending our introduction to East. It was time to move on to our first classes. Mine was on the first floor, my biology class, located in the corner at the south end of the long hall, toward Colfax Avenue. I figured out where it was when Frisell and I first entered the school. Frisell and Charlie had different first classes.

I walked into a magnificently large, brightly adorned biology classroom, paneled with tall windows facing out at fluttering butterflies and darting dragonflies, and the lush green manicured lawn. There were microscopes on the desks and a couple of rather large toads, and a couple of kids I didn’t know staring out the window. They must have gone to a different junior high than I.

Up the walls on the inside of the cavernous room, curling around the windows and crisscrossing the ceiling, twenty-five feet above our heads, were hundreds of purple flowering trumpet vines They repeatedly changed color from violet to dark purple and back as on a whim. It felt wonderfully warm and unnaturally humid, carrying the soft smells of honeysuckle and lavender.

In one corner was a gnarled apple tree that seemed to have moved, slightly. Was it an illusion?

Other kids entered the classroom and came in talking and laughing and they, too, just sat down at any desk of their choosing. Some guys fiddled with the microscopes.

Then that girl, Rebecca Gallegos, that waved at her friend from two rows ahead of me in the auditorium, casually walked into the biology classroom and sat down at the desk right beside mine. She seemed not to have been fazed by the large toad in the least. This was no illusion! Sort of angled toward me, she gazed toward the window as though she knew something.

With but a single turn of the head, a field of orange poppies bloomed outside in an instant throughout the entirety of the green grass and beyond. The red brick pathways ribboning through the gardens appeared to have changed to mustard yellow. A necklace of quail brushed by my legs as they scurried into the Kansas wheat grass growing beside my desk.

My Biology teacher walked from behind a curtain and introduced himself as Mr. Gallegos.

It was 9:50a.

My biology teacher had the same last name as the girl who had been sitting two rows ahead of me in the auditorium and was now sitting right next to me in my biology classroom. I had no choice but to fall in love with biology.

The biology teacher was Rebecca’s uncle.

With fireflies filling the hallways and toads warbling tales, with winged monkeys protecting it all from the high bell tower in the morning rainbow sunlight, three magical years at Oz began for each of us who were lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time.

We are a perpetual family still called the Class of ’69. In red.

Because, because, because, because, because…

Approaching East High School, as viewed from Colfax Avenue, 1966