From the Bob Willard Collection, Volume 6

October 12, 2020

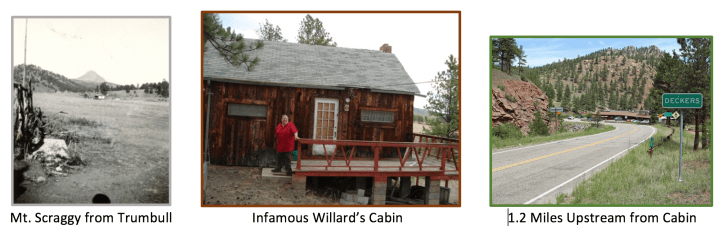

The Trumbull, Colorado Volunteer Fire Department was founded in 1952. Just 1.2 miles from the resort of Deckers, the Volunteer F.D. is nestled alongside the South Platte River, planted on the west side of a crumbling automobile bridge that staples Jefferson County to Douglas County. The V.F.D’s real location is at the junction of Colorado Highway 67 and an unnamed ½-mile long dirt road that begins in front of the white fire engine garage doors, follows the flowing river for a spell, and ends as beach sand at the edge of the South Platte River. The river yawns wide at that juncture with a cigar-shaped sandbar plugged in the center. That sandbar is populated by scattered bushes, shoulder height cattails, bamboo thickets, is colored by Indian paintbrush and seasonal weeds, is home to red ants, and brings occasional danger. Like grizzly bear. Rare. But once you’ve seen one grizzly down there, you’re on the lookout each time. But Willard’s Cabin isn’t located down there on the river.

If you drive along the hard dirt road that begins in front of the V.F.D. garage doors and travel for half of its ½-mile stretch, before the hard dirt pack suddenly transforms into a sandy version of Lakeside Amusement Park’s Cyclone roller coaster, with high crests and deep dives best-suited for high suspension 4-wheel drive trucks, or dune buggies with exaggerated red neck suspension coils, and during that short drive along the hard pack, you then accelerate up the steep hill on the left, with one slight right curl at the top, in total a difficult 85-yard ascent, you’d come to rest under a copse of Ponderosa pines. There’s room for about six to eight cars or trucks if the driver’s gave it some forethought and parked appropriately. But that many cars up at the cabin was very rare. After stopping your car, and after the dust settled in a couple minutes or three, you’d be staring at Willard’s Cabin. On the hill right in front of you. Facing the South Platte River down below.

There were two important amusement parks in the Denver metro area in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the timeframe of this opus: Elitch Gardens and Lakeside Amusement Park. Elitch’s was for rosy-cheeked families with strollers. It featured somewhat docile rides for children and a dance pavilion where local talent would play big band music. It was also home to the oldest summer stock theater in America (vaudeville founding in 1891) where you could enjoy live performances of Harvey (the 6’ invisible rabbit), and other productions that attracted statured actors like Douglas Fairbanks Jr (whose father, motion picture screen sensation, Zorro, attended Denver’s East High School), Van Johnson (WWII matinee star), Carl Betz (Donna Reed’s husband in The Donna Reed Show) and not to be outdone: Eunice Quedens. My apology. You are probably more familiar with Eunice’s stage name: Eve Arden, Our Miss Brooks. Each of them took to the stage at Elitch Gardens.

Elitch’s sold refreshing mountain stream snow cones with lots of colored syrups, and forest sticky cotton candy with lots of sticky. If you tossed a wooden ring around the neck of a coke bottle, which I never witnessed in all the times I was lucky enough to go to Elitch’s, you could win your own amusement park stuffed Harvey, albeit the less impressive 2’ visible species, rather than the 6’ invisible head turner. Elitch’s was the ‘white-hat’ amusement park. Mother’s with strollers.

Not at all like Elitch’s, Denver’s other amusement park, Lakeside Amusement Park, was the ‘black-hat’ amusement park. It could have been the location of the Dean Koontz horror story: Dragon Tears; the horror story that includes a wandering earth golem, out on the kill, that lives under the roller coaster of a long-deserted, long-closed-down, dark amusement park. That’s how to think about Lakeside Amusement Park. Monsters, golems and danger.

Lakeside’s aged roller coaster and crashing bumper cars attracted ill-tempered teenagers who sometimes brandished tattoos from cheap seedy parlors on East Colfax Avenue. No official driver’s license was necessary to crash the bumper cars, as rules and safety were the antithesis of the purpose of the ride. They didn’t care. There was no protocol. It was all the same to them. You could do what you want. And deeper into Lakeside Amusement Park was the creepy, maniacal Funhouse, with the mechanically amplified, fiendishly cackling fat lady, named Sal, rocking forward and back in her wood encasement above the promenade. Just approaching that part of Lakeside and cackling Sal squeezed your heart, and quickened the gait of youngsters… to get away… beyond her menacing stare. It only required a child’s imagination for her to instantaneously spring to life, jump her perch and run erratically amok, scaring the hell out of everyone. Kids would be screaming. And crying. And crashing into one another.

I believed as a kid that after the amusement park was closed for the day and deserted for the night, cackling Sal would return to her haunt somewhere in the bowels of the Funhouse where she would feast on lost children, tossing their little arm bones into a waste dump after sucking out the rich and bloody marrow. Like Koontz’s terror earth golem.

Jack Willard, Bob’s father, a man with dual entries in Who’s Who in America (first for writing a definitive book on the history of Colorado railroads, and a second time as an acclaimed international-tournament stamp judge) designed Willard’s Cabin on one side of a single sheet of graph paper while in chemistry class at the University of Colorado at Boulder in the late fall of 1950. Extra credit was not earned, not anticipated, nor awarded… nor deserved. It was just an okay cabin. Not an award winner by any stretch. It didn’t have to be. It was perfect for what it was: a simple one-bedroom exterior pine cabin design, with a partial-gutter green asphalt shingle roof that kept the indoors dry. One month after the cabin design was completed, approved, and cemented, Jack made Willard-love to Thelma, and nine-months later, their overly large son, Robert Steven (Big Bob) entered the world through Thelma’s ruptured birth canal, on October 12, 1951. It was at high noon, and Big Bob weighed 10 lbs 10 oz. He began life as a perfect 10, and I’ll stop there.

Once the dust from the cars settled, the front door of the cabin was accessed from the precarious cinder-block supported wooden deck and opened into the living room space with a large picture window on the opposite wall facing distant 8796’ Long Scraggy Peak beyond the South Platte River. We called the peak ‘Scraggy’ amongst friends or Mt. Scraggy to newcomers.

A rectangular grey Formica chrome table hugged the wall below the picture window. Other times over the years, two large comfortable sink-in cushion chairs replaced the Formica table. On the left wall upon entry was a beat-up couch that ended at an eight-rung wooden ladder that climbed straight up to the sleeping loft above. Two single mattresses were entombed by bedding and old blankets garnished with discarded Ruffles Original and Ruffles Cheddar & Sour Cream potato chip bags. Tubs of hardened spinach dip, bought at the Dino gas station in Sedalia, served as the loft’s ashtrays. A peppering of pretzel crumb sprinkles covered the space on the loft floor. One small single pane frozen window allowed spots of sunlight up there during waking hours, and offered a view of the outhouse in the evening.

The kitchen included a mid-size refrigerator, and a portable electric 2-burner Model S plug-in coil hot plate, with a partially melted black plastic pointed-dial temperature controller, and a 5-shelf narrow open pantry for canned goods. There were stacks of beans (not the green or yellow wax kinds), and Jolly Green Giant Whole Kernel Sweet Corn that was always ‘Picked at the Peak of Perfection’. And Freestone peaches. And a tower of small cans of Pico de Gallo, for those times when the Willard’s thought their cabin was located somewhere south, in Mexico. And there was always a jar of Celtic chutney that looked like a discarded petri dish.

Two small cabinets above the short kitchen counter held water glasses, and stemless wine goblets, and red disposable plastic cups, and chipped Sears ceramic plates, and stick-together peel-apart paper plates, and the pots and pans were down below, closest to the dirty floor. The one kitchen outlet, non-GFI, did a great job heating up the crusted double waffle maker with the unreliable, blinking orange indicator light.

Also included in the cabin was an oak-grain, contact-papered, utensil drawer organized with silverware, and two matching serving spoons from Thelma Willard’s kitchen back home on Monroe Street, and another peeling oak-grain contact-papered drawer that held everything else required for mountain cabin living: bottle opener, can opener, a combo bottle and can opener, half burned down old red candles, three-quarters burned down even older red candles, partially burned rubber bands, other rubber bands in a plastic bag bound by a partially burned rubber band, oxidized rubber band fragments as sharp as toenail clippings, pliers, leaky blue Lindy ball point pens, a couple screwdrivers (Phillips and blade), a small relatively useless claw hammer with one claw declawed, dust balls, food remnants from 1000 visits, three common 10d nails, fishing wire, corroded Lincoln head D wheat pennies with various dates, an Army knife, and several small boxes of Diamond wooden matches with worn out side flints. And discolored creased envelopes. And old postcards. And several old stamps that you’d never slide along your primed and moistened beer-drenched tongue. In other words, it was perfect; an entire hardware store in a mountain cabin drawer.

The wood frame around the narrow backdoor is where the nail was pounded to hold two plastic fly swatters; each with their ends curled up. It was from need, speed, and experience that located them smartly within easy reach of the kitchen sink, requiring little more than a slight left lean to grab one quickly, as the occasion demanded. Years later, a second common 10d nail, now leaving two in the drawer, was driven into the lower wood frame of the Scraggy picture window that was a proven attraction for the bulbous black Trumbull flies whenever either exterior door was left open; the front door or the one-step down-to-mother-earth backdoor by the kitchen. Enough fly swatters hung there for everyone to have their own. Everyone and Everything was considered! The yellowed 40-watt incandescent lightbulbs screwed into both outdoor porch lights worked… maybe. Couldn’t ever really tell. Trumbull flies congregating in the bottom corners of the living room picture window were mountain enormous with impressive lungs and low-throated buzzes that were a small growl. They appeared to wear little Army helmets and military goggles… and weren’t deterred by yellowed 40-watt incandescent lightbulbs. Sometimes things don’t go the way they’re supposed to go… things can always go wrong.

The sink shared the same wall as the large picture window five feet away in the living room. There was no running water in Willard’s Cabin although the sink had the holes bored to accommodate it should an upgrade ever be undertaken. Which never occurred. So, when you went to Willard’s Cabin, which was, let’s say, frequent, planning was essential as it required the transport of a couple 5-gallon Army Surplus water containers in case hydration or the washing of any of the dishes was put on the docket. Or to wash all of the dishes. Including the silverware. And Thelma’s serving spoons. And wipe down the counter. And the Formica table. Or wash your hands. Or face. Or non-speakables. Or hair with a lovely lavender aroma shampoo. Or douse the outdoor fire pit prior to a last second escape from the dust and grime in the summer. To race home to have a shower. With warm water. And a floor drain. And a washcloth. And a clean towel. And a comb. And toothpicks to try to carve the black crap out from under your fingernails. Culminating in a couple drops of Visine so you could retain your vision with an eyeball spritzing. Remembering to screw the cap back on for the next return trip’s application.

The outhouse for the cabin was up the treacherous hill, and was equipped with a hook and eye latch that almost kept the wooden door shut privately. Once sitting upright inside of it, it was easy to see who was scrounging around outside… if you were thus engaged during the daylight hours. Nighttime was different. Your ears became your eyes, your alarm mechanism to decipher not so subtle auditory differences between other inhabitants of the Rockies; from mountain squirrels scurrying about… to the occasional not so quiet brown bears… which, after all, are literally grizzlies. The largest one I ever saw was a monster drinking across the river, about an 1/8 of a mile down river/downstream/down wind, with a blonde streak down it’s back. It was a cabin trip with just Willard and me and he said at the time that it was the biggest bear he’d ever seen. Willard was a nature nut, more so than our other friends.

He’d approach a bear or a chicken hawk to get a closer look at it, or a rattlesnake to see how many maracas it had, advertising its age. But he knew to avoid young rattlesnakes. They weren’t experienced injecting their venom and were more likely to strike and cause death. Young rattlers emptied their load. As they age they learn how much venom they need to disable their prey.

But Willard didn’t approach the blonde-streaked brown bear across the Platte. Not even with the rifle cradled in his arms. He didn’t want to shoot it. Not with a .22, anyway. Maybe with a .45. Maybe. Bob was an avid duck, and pheasant hunter, and an average rainbow, and brown trout fisherman, and he would saw holes in the ice in winter to fish the frozen lakes. But he respected bears too much to shoot one. And he never did as far as I know.

Mary Roach, celebrated author, bestselling author, personally a living doll, wrote a great book aptly named Stiff, which describes all your options as a human cadaver. Turns out there are quite a lot of options beyond volunteering as a first-year medical student dissection study or being cremated or just decomposing during your dirt nap. She has a remarkable wit and writing style that entertains endlessly… no matter the topic. It’s a book I introduced to Willard as it was right up his alley… and mine. Birds of a feather. He forgot about the book before he passed, and chose the popular selection of cremation.

In Stiff, Mary Roach describes why the .45 caliber bullet is often the bullet chosen rather than the .38 or .22 or any other low caliber number. There have been extensive military studies as to the effectiveness of different calibers of bullet felling live targets. The goal was determining how much fire power it would take to down a living target when the living target had no preconception that it had been shot and should fall over. If you shot an enemy or live target that knew they should fall when hit, they might fall after being shot by any caliber bullet, but usually not if shot by little cousin BB. As Mary describes in the following insert:

Most of Mary Roach’s books are single word titles, supported by exceptional journalistic research: Spook (about afterlife in different cultures), Bonk (the science of sex), Gulp (a journey down the alimentary canal or as Blum might say: tongue to tushie), Grunt (curious science of humans at war). She wrote a book analyzing space programs in different nations called Packing for Mars. Many of us were irate when Mary Roach published a multiple-word titled book. Unsubstantiated, but reported still, even Mary wanted a one-word title: Tang. Her publisher blew it, and disagreed. Letters poured in suggesting she change publishers.

In Tang, uh, Packing for Mars, early on, she describes that in Japan, the very first test used to identify potential astronauts (or weed out potential failures) required each aspiring space flight applicant to fold 1000 origami cranes over a weekend lining them up on a string in sequence: 1, then 2, then 3 and so on and so on, 26, 27… 114, 115… 412… 732, 733… 810 – 821… 996, 997, then 998, 999 and finally 1000. Done. Those grading the test analyzed cranes 1-10 against cranes 991-1000: the first ten vs the last ten. Cranes 11 thru 990 were thrown out. They looked for consistency; not how good the cranes looked. The Japanese identified the #1 difficulty facing a manned spaceflight to Mars, the very first consideration in a lengthy list of issues that astronauts would face during a prolonged space flight, is boredom. Sitting for seven months in a can hurling through our inner solar system is a daunting task. If the cranes analyzed matched closely, passed inspection, then that astronaut applicant might advance up to the next rung of the spaceship flight ladder. The lauded Denver Post lauded the author, ‘Mary Roach is one of an endangered species: a science writer with a sense of humor.’

The outhouse at Willard’s Cabin had a wooden toilet seat that didn’t lift up, but imprisoned below, its own blue-colored Mt. Scraggy pyramid of plug and lime. It was like having their own Crater Lake, in miniature. I never understood why the outhouse was up the hill, rather than down the hill, from the cabin. Tim Crow’s parents had a cabin in the exact same area: Trumbull. In all, there were about a dozen cabins on that side of the hill, along Highway 67, tracing the South Platte; and whereas Willard’s cabin was the most isolated of all the cabins, and at one end to the far right, Crow’s cabin was the bookend cabin all the way to the left, and more a part of the ‘community’, of which there was very little. In fact, the only people that actually lived in that conclave of cabins, in Trumbull, was one old man and his old wife. They lived right next door to the Crow’s cabin. I’d been to Crow’s cabin as a kid about 50 times before I even knew about the cabin that Jack Willard designed in chemistry class. Both the Crow’s, and the Willard’s, located their outhouses uphill from their cabins. Because Crow’s cabin was closer to the road, two-lane Highway 67, than was Willard’s cabin, it made sense, for privacy reasons, for the Crow’s to not have their outhouse down the hill, where kids that had been tubing down the river might walk nearby, along the road, back to their tubing starting point, where river entry was easiest.

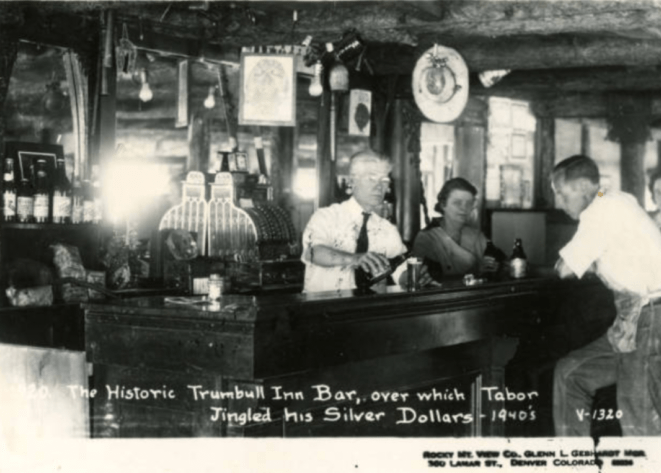

The other reason for the Crow’s decision to put their outhouse up the hill from their cabin, and not down closer to the road, is because of stragglers stumbling back to the ‘resort’ of Deckers from the Trumbull Inn Bar watering hole, which was the only building in Trumbull, other than the dozen cabins, and the volunteer fire department dual-door fire engine house. But the Trumbull Inn Bar burned down in the late 1940s, and repeated in 1968. The place was smelly, and dark, and a lot of sorrows were trapped in there over the years, with men’s hands curled around a Hamms, or a Schlitz, or an Old Milwaukee, or two, or three, or eight of them, supported by the bartender’s ear, and the ancient ornate cash register. The place smelled of Camels and Lucky Strikes. Old men wore wide suspenders. Whisky poured into shot glasses was wiped clean with swirling bartender fingers. The juke box played nothing I wanted to hear, from 45’s that never changed, from the early 1950’s. Empty napkin dispensers sat on tables that rocked back and forth. Being in the Trumbull Inn Bar was like living inside the kitchen drawer up in Willard’s Cabin, with all the dusty, old crap. No one could argue against the Crow’s not wanting any of the Trumbull Inn Bar patrons wandering up to their outhouse, no matter where it was located. And since the Trumbull Inn Bar had no actual clientele to speak of, it was rarely an issue.

The man and woman behind the bar may be Roy Hall and his wife, ‘Shorty’

With no adults planned to be around, it was easy to agree to going up to Willard’s Cabin once any one of us attained driving age… and could get the loan of a mother’s car.

The three black rotary phones in my house would ring in unison,

“Hello.” Me.

“Hey, it’s Bob. You want to go up to the cabin.”

“No thanks.” Hang up.

The phone would ring a second time,

“Nelson residence.” That’s my voice.

“I’ll pick you up in ten minutes.” That’s Bob’s voice.

“OK. I’ll be ready. Do I have to wait for you to fill the water containers? Or are they ready to go?”

“Fuck you. I already filled them. Are you going to go, or not?”

“Ya. I’m going. Are you bringing a towel?”

“There’s one up there.”

“Ya, I know. But are you bringing a clean towel?”

“No. I’ll pick you up in fifteen minutes.”

“You said ten minutes one minute ago.”

Twenty-five minutes later there is a knuckle knock at the door. My mom answers.

“Hello, Mrs. Nelson. Is Sam around?”

“Oh, hi, Bob. He’s downstairs in his room.”

“No, I’m not. I’m right here. I’ll be out in a minute.”

“OK. I’ll wait in the car. Goodbye, Mrs. Nelson.”

“Goodbye, Bob.”

I bring a bag with my Willard’s Cabin towel, an extra pair of white socks, and patterned underpants, and my bi-fold wallet. I throw my other pair of tennis shoes in the bag, in case we go tubing, in which case my shoes will get wet.

I started tubing down the Platte when I was nine years old with Tim Crow. The river wasn’t crazy with rapids, and didn’t look dangerous, but one step into it taught me that submerged river rocks are incredibly slippery, that you had to wear tennis shoes to protect your feet from slipping off the rocks or getting cut, and balance was essential. And I never had good balance. I grew up having bad balance.

I believe that every kid in my neighborhood had better balance than I had. All my life, just walking on a sidewalk, I’d weave a bit, without the ability to travel forward, in a straight line. To challenge my balance years later, as a post-college adult, I squeezed my eyes shut while in the middle of a blocked-off street, and couldn’t take but five steps before blindly, and wildly, putting my arms out, for balance. And I would have to catch myself from falling to the ground before I moved eight steps. Armed with personal experience, I boldly declared to two friends, Guber and Zuckerman, that the human being cannot walk twenty steps without falling over, if their eyes were shut. And then each of them one at a time, walked about sixty steps with ease, with their eyes shut, no meander, before asking if they could stop the experiment now.

I learned to get onto the large inflated truck tire inner tube, while still close to the river’s edge, and push my way out into the slow-moving skirt of the current, and then push some more into the full rush. There were a couple deep spots a short distance downstream that had huge boulders off of which you could jump into the river, and generally the river crawled through those spots. They were called pools, and when there were other kids in them, you could usually get one or two to help push the inner tube from its slow creep, and then you’d continue down the river, leaning back, basking in the sun, going down the river like Huck Finn. When you came around the bend, and could see the automobile bridge downstream, you’d have to begin to steer yourself to aim for a section that traveled all the way under it. Three of the six sections under the bridge were wired off from tubing; there was no way to tube through those. But you could avoid the trouble pretty easily… and continue for another half hour, angling toward shore, stop and get out, normally with just your butt wet from sitting down in the river, and your shoes wet, due to the liquid nature of Colorado rivers.

Everyone that’s been to the cabin has a story, or two, to tell. Miles, Joe Mark, Steve Irwin, Tim Crow, the ‘Gub’, Zuckerman, Charlie Wagner, Gottesfeld in his yellow Ford Fairlane 500 top-down convertible, Gary Buckstein (who shot a squirrel with Willard’s .22 rifle, allegedly so Bob could make a squirrel-tail hat, which once shot, Bob said: ‘Nah. I don’t want a squirrel-tail hat anymore.), Blum, of course, and later on Ben Kempner, and Ben Cohen, and Kathy Kreuger, and Rebecca Gonzales, and Cindy Toule, and Kay Willard’s friends (Kay was Bob’s younger sister by one year), and many others I never knew. Even one-timers from out of state, like Bob Gregory, remember Willard’s Cabin, and has a story to tell.

Once we turned 16 and could drive, we’d go up with little notice and no planning. I had a key to the cabin door, and I’m sure lots of people had keys, too. If I were going up with Guber and Zuckerman, I’d check in with Bob, and if he couldn’t go, he’d always say go ahead, unless his parents were going to be there. That’s the one thing we always wanted to avoid. Not because there was anything wrong with Jack or Thelma… it’s just… well, you know. They were old, and they were parents, and they probably go up to get away from Bob, so why would they want to see me, and some other guys up at their escape cabin. Plus, they didn’t even know Guber or Zuckerman, and it was probably better to keep it that way.

One rule of high school age and older: the less communication with parents, the better. The less they know, the less we have to remember. And the more beer cans, and cigarette butts, and marijuana joints that Willard’s parents find up there, the more likely Bob will ask for the key back. And then the whole Indian-giver thing might rear its childish head, and we’d have to get into that back-and-forth, and ultimately you knew you weren’t going to give your key back to Bob, and he probable knew he wasn’t going to get it back, so the verbal exchange was a waste of time, and we had too many other things to do than waste our time on that circular argument.

Although I have to admit that there was one time that Jack and Thelma did show up unexpectedly. I saw them driving over the bridge down by the volunteer fire station, and screamed, “We’ve got to clean up… fast!” to Guber and Zuckerman, and as Willard’s parents entered through the front door, we exited out the back by the kitchen, but they knew we were there anyway. They parked their green Ford station wagon next to my green Barracuda hatchback; which was my parent’s car. And since Jack Willard drove home from work, from Public Service of Colorado, by going right by my house, every day, he’d seen that car at my house 1000 times. I’d wave to him from the side hill, or the flat parkway, as he drove by around 5:30p, for ten years. So, there was no escaping that he knew the car, and knew I was up at their cabin. The day we got caught up at the cabin by Jack and Thelma showing up unannounced was pretty enlightening because they were really cool about the whole thing.

I said: “Sorry for being up here.”

And Mr. Willard replied: “Drive safely.” Thelma didn’t speak. She just unpacked.

So that was civil and pretty good. Except I couldn’t move my car because his station wagon was too close for me to get out, and he let me re-park his station wagon for him. As I returned his keys, I brought into the cabin their last bag of groceries, filled with more cans of Pico de Gallo.

When my father bought the 1967 green Barracuda hatchback with the 283 engine (something I cared absolutely nothing about, but Willard did), Willard and his grandmother, who lived right next door to him, in their duplex, he being at 1025 Monroe and she at 1031, went out and bought a car for her, so said Bob. If you haven’t met Willard’s grandmother, she was 75+ years old, small, short, frail, had no muscle tone, weighed nothing, and needed help guiding a spoonful of soup to her thin shaking lips. She may not have known there was a Willard’s Cabin anymore. She was Bob’s father’s mother. His mother’s mother was also ‘alive’, older than his father’s mother, but she lived on 1863 S. Gilpin Street. And I know she didn’t drive. She couldn’t see. But would have been perfect for the bumper cars at Lakeside Amusement Park.

Bob Willard talked his grandmother, on his father’s side, into buying that blue 1967 Ford Mustang coupe with a 289 engine (something I still didn’t care about, but Willard did) that had a 3-speed stick shift on the column with a clutch. They bought that three-on-the-tree car three days after my father bought the Barracuda. I saw Willard’s grandmother sit behind the wheel one time, in front of his house, on Monroe Street, and she was too short to see over, or even through, the steering wheel. She couldn’t even reach the rearview mirror to adjust it. Bob’s grandmother never drove that car. I’m not sure she had a driver’s license which would not have prevented her from crashing the bumper cars at Lakeside.

Stick shifts were something I did know something about because the first car I drove was Tim Crow’s parent’s red 1963 Chevrolet Corvair. Tim was born in February so he had me by eight months. I was one of the late kids to get to drive, with a late October birthday, but Tim would take me out months before I had my driver’s permit, and let me drive on a dirt road out in an unincorporated area of Aurora. It was thrilling to be able to drive, notwithstanding the car had a stick shift. I can still remember the ominous weight of the car the first time I put it in gear. Tim Crow taught me to drive. I don’t know who taught Willard, but he was a good driver. But it wasn’t Tim who taught Bob.

Willard and I went on driving trips more than a few times together. The first time we drove to LA, to visit my cousin, was in the summer of 1968. A lot of things happened on that trip. Let it suffice that the sleeping bag that caught fire, that was in the hatchback portion of the car, was put out fairly quickly. It took us 19 hours to drive home to Denver from San Jose, and that seemed pretty fast. There was no speed limit in Nevada, which helped. At 110 mph, the car shook a bit, so we agreed not to exceed 105 through that stretch.

To reiterate, everyone that had ever been up to Willard’s Cabin, had stories. Sometimes the stories get distorted. This is one, in particular, that has had some embellishments over the years, from those who weren’t present at the time, and are only embellishing it, without a full understanding of the actual details.

One July 4th, in the summer of 1971, Zuckerman and I went up to Willard’s Cabin, and Guber was going to be driving up a little later in the day. He had some festivities to attend at his Uncle Dave’s house, on a lake, in southwest Denver. Somewhere in Lakewood. Fancy house, fancy neighborhood.

Zuckerman and I had walked into Miller’s Supermarket on 7th and Colorado Blvd, on the way up to the cabin, and grabbed a few New York strip steaks, including one for Guber. Believing that the statute of limitations has by now run its course, when I say we ‘grabbed’ a few steaks, I don’t mean to imply that we bought them. We didn’t have money for New York strips at that moment (or several other moments back then), so we just walked in, put a few New York strips in our pants, shielded by the zippers, and walked out. Not anything to be proud of, and there is no horn tooting in any of that. ‘Just the facts, Ma’am,’ as per Sergeant Joe Friday on Dragnet.

By now, Zuckerman and I are at the cabin smoking pot, and drinking beer, and listening to music from the speakers I had brought along with us. They were these huge Wharfdale speakers. Each one weighed a ton, and the Grateful Dead album American Beauty sounded fantastic. Even Aqualung sounded good. Willard had left his Aqualung album up there, and he was a huge Jethro Tull fan, and would sing along with it with his booming stentorian voice that later performed at karaoke bars, throughout Colorado… Willard earned a favorable reputation over the years for his singing. It was his escape, and his pleasure, and his solace, and Aqualung was his favorite album since its original release. He’d play it non-stop in his basement bedroom at 1025 Monroe Street.

Zuckerman and I were pretty much instant Jerry Garcia and Grateful Dead fans, as was Karle Seydel – original Deadheads. Karle would listen to Workingman’s Dead until the needle would give out on his Gerard turntable, and buy a new diamond needle at Wells Music later the same day.

Zuckerman and I were pretty much instant Jerry Garcia and Grateful Dead fans, as was Karle Seydel – original Deadheads. Karle would listen to Workingman’s Dead until the needle would give out on his Gerard turntable, and buy a new diamond needle at Wells Music later the same day.

Later in the afternoon on the Fourth, up at the cabin, around 5:00p:

“Isn’t that Gub walking on the road, on the other side of the river?” observed Zuckerman.

Looking out the picture window facing Scraggy, I responded, “I think so. Yeah, it must be.”

“Why would he be walking?”

“I don’t know. But it’s definitely Guber.”

We get into my car, and drive down the hill, continue onto the flat dirt road past the volunteer fire department building, continue onto paved Highway 67, turn left over the bridge, and drive ½ mile down to a walking Guber.

“What are you doing walking along the road? Where is your car, Rudy?” (Guber’s nickname was Rudy, or Gub, or Mr. Tuber. He’d usually answer his phone, “Tuber speaking.”)

“I ran the car into the river,” was what he said.

“What?”

“Yep. I missed a turn.”

“Where?”

“About a mile up the road. I drove into a bunch of bushes, and reeds, and couldn’t back out. The car is stuck.”

Zuckerman and Guber and I drove to his car, and see only its wide metal ass sticking out of the bushes, and the three of us were able to free his car. Hallelujah! Guber was a pretty big guy, and strong. He had been a Truck Tire Vulcanizer at Gates Rubber Company, on South Broadway, in Denver, during the summer. To do that job, Guber had to lift 70-pound rubber tire cylinders up over his head, and drop them into the vulcanizer, which was like a huge oven, that would ‘form’ the truck tires into what you’d buy at the store.

And Zuckerman was a strong guy, too, but not as big as Guber. Guber got Zuckerman a job at Gates Rubber Company as a Fan Belt Builder, which required operating a horribly large finger-eating contraption with tons of minute controls, and Guber got me a job there, too, as a Tire Builder. I’d have to slap this piece of rubber onto that piece of rubber, and a larger piece of corded rubber, and push foot pedals exactly the right amount of time, with an exact amount of pressure, for the slapped together rubber pieces to make one revolution, to form a cylinder, and then take a hot knife to spread the cylindrical edge together, and if the tire demanded white walls, I’d include that in the recipe, and then I’d leave all the tires that I built for the shift inspector to look at, after I’d punched out for the night. Then, put on my steel-toed shoes again, the next night, prior to driving to work. We were all working the graveyard shift. We had to punch in and out, and the entire building smelled strong of rubber poison.

Each night for a week, I’d return to work to find every one of my tires rejected with a white chalk X on them, so I’d spend half the shift using some liquid rubber decomposer on the cylinder to help take it all apart, to save all the rubber ingredients that I had slapped together the night before. Each tire took a long time to disassemble. Like 20 minutes. I just gave myself underserved alacrity credit. It probably, more realistically, took 40 minutes to break the damn things down to their component parts. Gates Rubber didn’t want to throw away the failed tires. Too costly. I never built a tire that passed inspection… thankfully. You were all, unknowing, safe from purchasing any Gates Rubber Company tire that I built… or didn’t build, as it turned out. I got paid my 40-hour paycheck with the extra 10% for working graveyard. I lasted two weeks. Two paychecks. No drivable tires.

Back the 4th, we returned to the cabin with both cars, Guber’s and mine, and Guber looked a bit shook up. Once we got inside, and turned the volume of the music down a notch, or two, or three:

“How did you drive your car into the reeds?”

“I spent all afternoon with a large butcher’s meat hook in a line with a bunch of other guys from houses all around Uncle Dave’s house, going through the lake in a line, trying to find a water skier who had tied his ski to his foot, and had drowned.”

“Are you serious?”

Well, ya, Guber was serious. He’s not going to make up a story like that. It was a story covered by both the Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News on July 5th.

Guber left the lake after his second hour of uninterrupted trolling, and when he’d left, they hadn’t yet found the kid. He got in his mom’s car, in front of his Uncle Dave’s house, turned the ignition key, headed for the cabin, drove into the cattails and reeds protecting the Platte from inebriated drivers, started walking down the road toward the cabin, and later we cooked the New York strips on the outdoor fire pit, and we were all happy that Willard’s parents hadn’t decided to drive up for the holiday.

And Guber was especially thankful that he hadn’t been the one to find the kid with the meat hook, and was just glad to be up at Willard’s Cabin. Because we were all always happy, and glad, when we were up at Willard’s Cabin. Circumstances didn’t seem to have any influence. It was its own world.

Great memories and thanks Sam.. Loved it. Much easier to read on the big screen than the phone.. Cannot wait for the other stories..

LikeLike