From the Bob Willard Collection, Volume 3

July 26, 2020 First Edition

The morning began as usual at our breakfast nook table. The cleaning lady had come the day before and gave special attention to the kitchen and the nook. They were clean but not any more clean than when my mom cleaned. I didn’t know why my mom needed someone else to clean our house.

My mom scrambled two eggs and toasted an English muffin and poured me a small glass of orange juice and a larger glass of Royal Crest Dairy whole milk.

The orange juice was from Miller’s Supermarket but the Royal Crest was the last milk that was ever delivered to our house by Johnny, our 7:00a milkman. His route had been cancelled. I didn’t have a real appreciation as to what that meant. I was ten years old. But my mom had that face she gets when the glass of foamy water cleaning my dad’s dentures gets knocked over.

The only picture my mom had of Johnny delivering milk to our house was taken over two years ago. He was a nice man. The lady back by his truck looks like it might be Margie, a neighbor who lived three houses down the alley. Well, she lived three houses down the street, too. Her hair is darker now. It seemed early for Margie to be walking around outside. She had outgrown school age.

All my mom had to do was fill out the milk form the night before and leave it in the milk box. The milkman drove down our alley twice a week, checked the milk form and delivered what was checked off on the form.

‘Sammy, do you want me to order anything special from Johnny?’ It was okay for my mom to call me Sammy, but nobody else. I’d answer her but not anyone else if they called me Sammy. I was ten years old; not six.

Sometimes she checked off the cottage cheese box. Sometimes she put a checkmark next to the chocolate milk, but she didn’t order it often enough. It was Royal Crest chocolate milk, not in the same league as Hershey’s. Closer to the Nestles chocolate milk with the singing cow. But Royal Crest was acceptable. I guess Hershey’s and Nestle’s didn’t have milkmen in our neighborhood. Now our’s would be gone, too.

My mom thought she should leave a $5 tip in the milk box for the milkman since it was his last day and my dad said it was okay. He didn’t have much to do with finances. He just made the money and my mom spent it and paid for stuff like bills. My dad would have to sit at a desk or table to pay bills but he had a bad back and preferred to lie down.

My mom was never extravagant or goofy with the money. She was just a mom like Frisell’s mom, or Willard’s mom, or Tim Crow’s mom or all the other moms in the neighborhood. Frisell and Willard and Crow were best friends of mine. I had a few others.

If asked, I guess the eggs and English muffin were probably from Miller’s Supermarket just like the orange juice.

It only took me two minutes to eat, gulp and swallow because Frisell was already waiting outside to walk to school, and then my mom handed me 25¢ to slip into the front pocket of my pants to buy the school lunch.

‘Thanks, mom,’ and I was out the screen door and headed off for school with Bill Frisell. There were a lot of other kids named Bill, so we just called him ‘Frisell’.

Bird songs filled the air and there were dragonflies and the sky was a perfect Colorado mountain blue. It was sunny and warm.

I write about those things now, but I didn’t care then. I just cared that this was the second to the last day of school… and then it would be summer vacation. Pretty much every kid thought exactly the same thing. It’s all anyone could think about.

Frisell was carrying his clarinet to school that morning but I’d left mine in the band closet over night. He brought his clarinet home to practice but I didn’t want to over-practice so I left mine at school. I was committed to music but Frisell was more-committed, as though any of it was going to make a difference later in his life.

After checking into our homeroom for notices and attendance taking, the first class for both of us was Band.

Band was a snap – we all just goofed around more than usual on that second to the last day of school even though we still had to take our seats and toot notes for like ten minutes and then Mr. Fredrickson just let us stop because none of the kids were paying any attention. After all, we were only one day from summer vacation.

Expectations the whole day in all my classes were at their lowest of the year. Maybe the last day before Christmas vacation gave it a run.

Next to Gym, band was the easiest class you could ever have. But if you didn’t take band, you were probably in Mrs. Joy’s choir class, and that class was for sure as easy as band.

They had kids in Mrs. Joy’s choir class that couldn’t sing at all. I heard Bobby Siler sing once. It was out on the playground. It was raining lightly. But still.

He should not have been in Mrs. Joy’s choir class. Whatever she was teaching wasn’t working for Bobby Siler. I could sing 10X better than Bobby Siler and I wasn’t even in choir class. But I’m pretty sure he was in her class. He wasn’t in band. I can tell you that much. There was no instrument that Bobby Siler knew how to play and there wasn’t any song he knew how to sing.

Charlie Wagner left his two-piece metal clarinet at home so he didn’t have to toot that day but he sat in his music chair anyway and looked dumb without his clarinet.

After band, I had Arithmetic. Our teacher, Mr. Mulholland, marched in the Philippines in WWII. Someone said that there was something wrong with the march. I liked Mr. Mulholland. It was a girl named Jane and I that were his top students. She was pretty smart. I was good at adding and subtracting and multiplication and ahead of most of the kids when it came to fractions.

Mr. Mulholland let us just play a game with addition and multiplication puzzles. There were some fractions, too. It was fun. Quizzes were over for the year but I always beat the quizzes.

Next came my most hated class by a Colfax mile: Social Studies. That was my period 3 class for the entire semester. Thankfully, after Social Studies was lunch.

That’s the morning schedule that I was given in Homeroom the first day back to school after Christmas vacation. Band first, followed by Arithmetic which I was really good at, then crummy Social Studies and finally Lunch.

When I looked at my schedule, the problem was easy to spot.

I knew where the social studies classroom was located in room 321. It was up in the back corner of the third floor — the farthest classroom in the whole school from the lunchroom cafeteria.

I was never gonna be first in line for lunch. Or second or third or fourth. But I was agile and pretty quick. Willard’s class before lunch was just one floor above the lunchroom so he got down there easy, even though he was kinda slow. He was big, and he was slow because he was big.

Sometimes the volunteer lunchroom ladies fell behind schedule which allowed me time to get down to the lunchroom in time to butt in line up near the front where Willard was standing. Billy Snyder didn’t like it much when I butt in line but he was smaller than me, and a lot smaller than Willard. A lot of the time that’s how things got decided at my elementary school.

I never really grasped what the name ‘Social Studies’ meant. You know, the title. Social Studies. It was so different from the names of all the other classes that we were forced to take.

I wasn’t the only kid that went all the way through elementary school and never really understood the name. Frisell didn’t know. Tim Crow had no idea. Kubly? Nope. Not really. I know for sure that Willard didn’t know, although it’s the kind of thing he might know. He’s good for that kind of stuff. Linda Hart didn’t even know! And she was voted in as our class representative, again, like every year.

I did know what the teachers did to us in social studies. I can’t remember any examples of what they tried to teach us but I know everything we learned took place somewhere back in the past, so it’s technically, history. Even people talking on the #13 city bus that went down Madison Street said that Social Studies should be called History.

On this last Wednesday for the whole school year, the red school bells lining the long hallways clanged noisily to end the period 3 class. It was time for lunch. I was watching the clock and jumped up and slammed down my social studies desk top and headed down to the lunchroom cafeteria for Teller Elementary School’s final Wonder Bread sandwich day.

It was smart for the school to schedule a Wonder Bread lunch day on the next to last day of the school year because then the volunteer lunchroom ladies working in the cafeteria didn’t have to warm up anything or cook anything and make a big mess with a lot of pots and pans and dishes. They were as sick of making the food as we were of eating it.

Some kids still brought their lunch to school in brown paper bags with their names on it.

Most days during the week the volunteer lunchroom ladies made hot food like oatmeal hamburgers in plain buns. String beans or corn. But we didn’t have to eat salad. They didn’t serve salad in elementary school. Why would they?

I remember the first time the volunteer lunchroom ladies made a hamburger-french fries combo. We were in 4th grade. They topped it off with green wiggling cubes of lime jello and I thought that was pretty neat. And it also came with a cookie because it was on a Tuesday.

Tuesday was always cookie day in the cafeteria at Teller Elementary. But we didn’t have the hamburger-french fries-green lime jello cube-cookie combo that day. That’s because that day was the final Wonder Bread lunch day. And besides, it wasn’t Tuesday. It was Wednesday. They gave us oatmeal raison cookies the day before and I gave mine to Willard. I wasn’t going to eat an oatmeal raison cookie because I didn’t like them.

We never did much in homeroom. We had to check in there for ten minutes first thing in the morning. They just wanted to see if we came to school or if we had a sour stomach or if our skin was yellow or if we scraped our knees on the playground. And to tell us something important if there was something important that day which we forgot five minutes later. One day they took Denny Blum’s temperature in homeroom.

As I hurried down the metal stairs to begin period 4 lunch, the Wonder Bread sandwiches were already being prepared by the volunteer lunchroom ladies who wore stretched-out black hair nets over their heads. I guess they didn’t want to get grease splattered on their scalps even though it was Wonder Bread sandwich day and they weren’t creating any grease. One of the volunteer lunchroom ladies had an odor but if you sat far enough away, you couldn’t smell her while you were eating your lunch.

The only two rooms in Teller Elementary School larger than the lunchroom cafeteria were the auditorium, where band class and school assemblies were held, and the library, my homeroom for that last semester.

Homeroom wasn’t graded. I would have gotten an A for sure.

Wonder Bread was the most popular sandwich bread at the end of the 1950s and the early 1960s. Its slogan boasted, ‘Helps Build Strong Bodies 12 Ways – look for the red, yellow and blue balloons printed on the wrapper’.

I didn’t have a strong body. I knew it. I was meek. I guess that I didn’t eat enough slices of Wonder’s award-winning, prized bread.

I focused my eyes on my upper arms by staring in the bathroom mirror. I could not detect my arms getting any stronger. I’d flex my muscle where the bicep was supposed to show up, with the door closed and locked, and lean in real close up to the mirror. I’d look real, real hard, but there was no discernible bump. No bump at all! Even squinting didn’t help.

I wondered if Wonder Bread’s slogan was a joke. I wondered if the slogan meant that their fantastic, desirable bread built already strong bodies 12 ways.

I thought I had been eating as much Wonder Bread as even the older kids, like George Kawamoto or Gene Cassidy. They were neighbors. In fact, inside my mind, I was an aggressive Wonder Bread eater. I ate it constantly. Maybe if my mom was toasting Wonder Bread rather than English muffins it would have made a difference.

Most of the moms in the neighborhood bought Wonder Bread. Even Blum’s mom. Denny Blum was a real close friend who lived a couple blocks away. Big Bob Willard’s mom bought loaves and loaves of Wonder Bread and so Willard ate loads of it. Big Bob was another real close friend who lived a couple blocks away but not in the same direction as Denny Blum.

There were two choices of Wonder Bread sandwiches to pick from at 5th Grade’s final Wonder Bread lunch bonanza:

1 Baloney – a single slice that concealed 1/2 tsp of crusty mayo and a couple spots of soft-squeeze, yellow southern mustard. The baloney sandwich had a little green sidecar buddy in the form of a gerbil pickle.

The baloney also came with a decent package of hard shoestring potatoes — the ones that always contained at least one or two or three long burnt black shoestrings; called ‘matchsticks’ by the black hair-netted lunchroom ladies. I liked those hard shoestring potatoes. But the baloney sandwich didn’t interest me.

Willard loved the baloney. So did Bill Jent. Bill Jent was more Willard’s friend than mine, but I knew him pretty good. They ate the baloney sandwiches while facing each other at the cafeteria picnic-like lunchroom tables.

The other Wonder Bread sandwich on that last Wednesday was only available to kids that were registered as free from peanut allergies. They were the kids that submitted the Peanut Allergy Free waiver form with both parent’s signatures on it back at the beginning of the school year. Charlie Wagner’s dad had already died so they only made his mom sign the waiver.

I was on that list. So were the majority of kids. My mom brought the form over to the school the day we had to turn it in because I left it at home.

The only kid that I knew of with peanut allergies was Bobby Siler. Big kid. Real large head. Let’s see. What can I tell you about him? He didn’t speak much. Maybe his throat was always slightly shut with peanut allergies. I didn’t know. I didn’t spend any time with Bobby Siler. I can’t remember ever having a single conversation with him. He wasn’t a good singer, I can tell you that much.

Anyway, for those kids that didn’t want the baloney sandwich, the other Wonder Bread sandwich of the day was:

2 PBJ: Chunky Peanut Butter with Grape Jelly

As an aside: It’s not essential to the story but back in September, at the beginning of our 5th grade school year, I made an attempt to get the cafeteria lunch ladies to replace the grape jelly with strawberry jam. The grape jelly was runny. I preferred a thicker, meatier jam. Jam had pieces in it and jelly didn’t. That’s how you could tell.

Turns out almost every kid I talked to over the summer preferred jam to jelly, too. Some of them told me to request the jam once school started. It felt like I might be being set up. But I thought about it and figured a plan. I got up the nerve on the first day to talk to Linda Hart about it.

Linda won the vote to be our class representative every year with astounding majorities. I figured she would win this year, too. The election results always had numbers suggesting stuffed-ballot majorities, but there was no ballot stuffing going on. Linda was just that good. We didn’t even know what ballot stuffing even meant. Like the name Social Studies.

We had started voting on sheets of paper in school in 2nd grade. We were just starting to be able to write our names that you could actually read.

Linda was tall and classy and steady and kind and in the past year her hair was always neat like it was pampered real nice on her walk to school in the mornings. Didn’t seem possible. Linda was just that good.

I rarely talked to Linda throughout elementary school because I discouraged myself, comparing her lofty standing in our classroom hierarchy to my sub-basement standing. We both got good grades; I was close to an ‘A‘ student every report card, and I suspected that so was she. We had some classes together and one semester we had the same homeroom. But she was classroom royalty and from some angles you could just about see her glistening crown. Linda was that good.

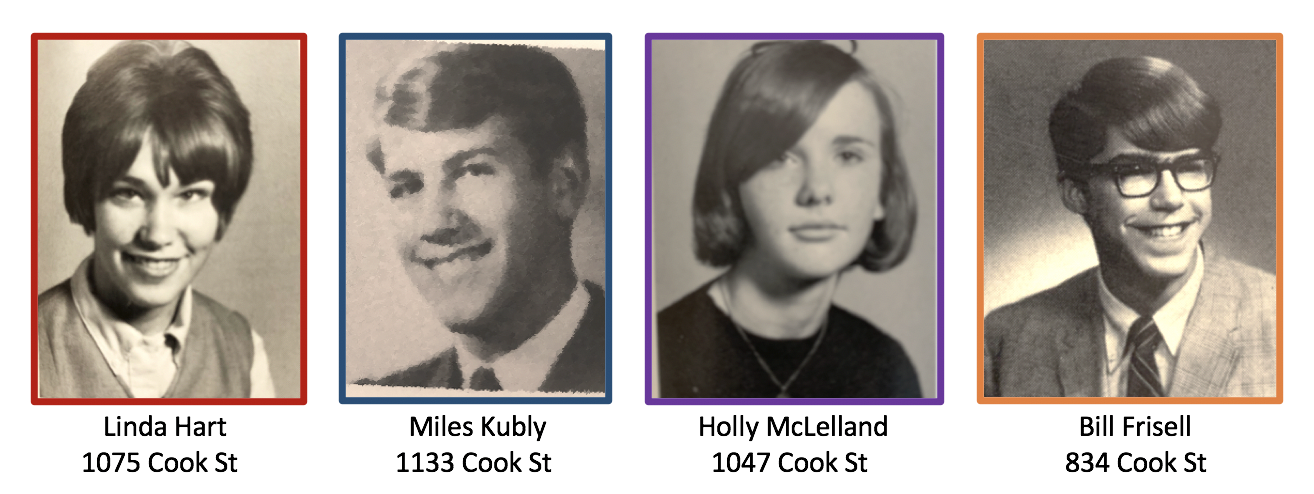

Linda grew up on Cook Street, the same street that I grew up on, and that Frisell grew up on, and that Kawamoto grew up on, and that Miles Kubly grew up on, and Holly McLelland lived two doors from Linda, also on Cook Street, and even the entire O’Block family lived right across the street from Linda Hart, including their grandmother, who smelled even more than the lunchroom lady volunteer.

Maybe all grandmothers smell. I never had a grandmother. They were all in heaven by the time I showed up. I still don’t know when they went to heaven or why they died. I could find out. Ask my older brother. Maybe he knows. Maybe my grandmothers never smelled because they died early, before they started to decompose and could still snore. It coulda happened that way.

There were lots of kids and families that lived on Cook Street. Above are pictures of four of the kids I mentioned. This lineup are their high school pictures years later. Their elementary school pictures don’t look as much like them now. The younger the age of a kid in a picture, the tougher it is to identify that same kid when all grown up. It’s impossible to look at a kid’s sonogram picture and match it to what they turned into as a kid, much less as an adult. I can’t even figure out a reason to have a sonogram picture. As far as I know, my mom didn’t have one of me.

Miles and Holly and Bill attended the same barber but Linda went to a professional hair stylist. Linda was that good.

Cook was a good street, even though the Rainwater family lived on the same block as Linda; but Linda lived on the corner and the Rainwater’s house was eight houses up the block toward me, and on the other side of the street.

One of the Rainwater kids shot and killed a cousin or a brother with a rifle right in their house. Or maybe it was in their backyard. I heard both. Neither fully confirmed. Either the kid that did the shooting was named Stanley or his cousin or brother that got shot was named Stanley. I never got that straight either, but the guy that would remember the whole thing, including the names and special mishap particulars, was Big Bob Willard.

He remembers more than I remember a lot of the time. He didn’t grow up on Cook Street, though. He grew up on Monroe Street. That’s two blocks over. Anyway, the Rainwater killing happened after we were all done with elementary school, while we were in junior high, but no one was surprised when word leaked about it. It’s not the type of thing that can be kept secret. Murder had come to Cook Street. Maybe it was accidental murder; not premedicated, as they say.

I never played with any of the Rainwater kids. And I would play with darn near any kid that was available to play with at any time during the day. Any kid. I didn’t even have to like them that much. I’d still agree to play.

This is how playing got started.

A kid would say, ‘Do you want to play?’

Nothing specific. Didn’t matter.

‘Do you want to play?’ That’s it. Or shortened to ‘Wanna play?’ if you already knew the kid and had played with them before.

When I was allowed to start to use the telephone, I’d call Frisell and say,

‘Wanna play?’

And Frisell would say, ‘Ya’.

And we’d get together and play. Went on that way for a spell.

As we got a little older, we’d get more specific and would say something like,

‘Wanna play pingpong?’

And Frisell would say, ‘Ya’.

And we’d play pingpong or do something else. Maybe throw the ball around or play tetherball down at the school playground when there wasn’t anything else to do.

All day and all night that yellow tether ball would hang down on the end of the rope and nobody ever stole the thing. Nobody wanted it. Anybody could have just cut it off. Tether balls basically sucked and the ‘sport’ of tetherball sucked, too. There was nothing else you could do with a tether ball with that hard black rubber loop stuck to it.

If you listed all the different kinds of balls from childhood, from best to worst, tether balls would be at the bottom of the list. Even below golf balls. No kids played golf in the 1950s and 1960s. And 1970s and 1980s. Maybe a few in the 1990s.

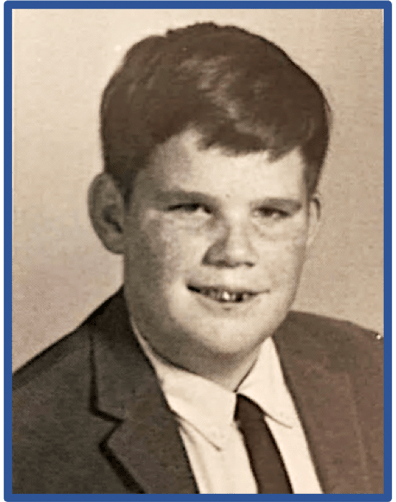

A more formal introduction to Bob Willard, aka Big Bob, is necessary now. Basically, Willard was my partner in crime as we grew up. I guess you wouldn’t be lying to say we were troublemakers when we were together. But he’s the kid that everyone knew stirred the troubled pot. Just take a gander at him. You can just see the trouble he can cause.

He’s the kid that brought razor blades to school in junior high. He’s the one with the Cherry Bombs and M80s. He had the first pocket knife and he was the first to figure out how to strike wooden matches. He got the orange paint on my white band shirt that I got blamed for. He liked to catch snakes. He’s the kid that interrupted a fight at Tank Park across the street from junior high when the ‘scheduled’ fight between Gene Cassidy and Kip Reed didn’t amount to much. He just wanted to put on a show. So he jumped in and fought both Gene and Kip. He liked limelight. He never hurt nobody.

Oddly enough, Kip Reed was on the playground and I was on the playground near him when he said that he heard on his transistor radio that he wasn’t allowed to even have at school that President Kennedy got shot.

I’m just projecting but I think Kip was the dumbest person in our class. Maybe the whole school. He was a big kid, probably held back two years and had a bandage on his thigh where he says he got stabbed. 7th grade and Kip Reed got stabbed. Nobody believed him when he said that President Kennedy got shot.

Big Bob’s parents had a cabin up on the South Platte River by Deckers. Big Bob used to shoot rifles at cans that he set up on the fence and on top of rocks. He was shooting .22s.

He’d shoot at the trees and shoot at fish in the river. He didn’t hog the gun. He let others shoot it. I did many times out the cabin backdoor. I didn’t carry it around like I was hunting. It wasn’t hard to shoot the gun and hit the target. But his dad made him responsible, and he had to learn how to disassemble the guns and knew how to clean them.

In high school, if we were up at his cabin, Willard would mosey down the hill toward the Platte River, and shoot out the only street light on the dirt road. Just blow up the whole thing. The local authorities would replace the light the next week, and the following week after that, Big Bob would mosey again and blast the light to smithereens, again. These are the things that were Big Bob.

Wiped dirt on his pants. That didn’t make him special. We all did.

If you looked closely at the picture of Big Bob Willard earlier, you can see that his upper front teeth were made of sheet metal. Like ‘Jaws’ in James Bond except Willard’s were just the top front teeth. Jaws had a mouthful. Or I guess a jawfull. He could bite through nails and I guess he could bite through Elcar fences if he lived Denver.

I don’t know what kind of sheet metal they used for Big Bob’s top front teeth. They used to be normal teeth like what most animals have, like horses and donkeys, but Big Bob broke them off tripping on the sidewalk, smashing them into a concrete step in front of his house. This explanation according to his little sister. Or in a fight with an older kid if you wanna believe Big Bob. His parents bought the sheet metal replacement teeth because they were less expensive than normal looking human teeth or horse teeth.

The word ‘Leader’ could have been sewn onto the back of Linda Hart’s clothing. Following my first day of 5th grade plea to Linda, she agreed to present the ‘strawberry jam‘ request at the class leaders meeting in early October.

It was in that October Student Council meeting that Linda was told by school administers that our class (5th grade) could not make requests like my proposed jelly swap until the beginning of 6th grade… and so that’s what Linda told me that she had been told. I communicated the disappointing news to my classmate pals while we were out on the playground later that same day.

Up until I started telling everyone on the playground about the strawberry jam rejection, the only two people in our class that knew about it was Linda Hart and me. Which made me feel special.

Nobody really seemed to care about the year-long strawberry jam request delay. Maybe they actually had tricked me into asking, trying to push it. Whatever the situation, Willard used the disappointing news to grab a worn-out four-square ball out of little Greg Jones’ small hands and punted it. But Willard didn’t just punt it… he launched it. He put the ball in orbit.

It was a classic Willard beauty, which stopped time as it soared over two Chinese poplar tree tops, and ricocheted off the roof of Teri Adams’ house and into her backyard. She lived directly across the street from the playground on the corner of 11th and Garfield. Willard just used the jam replacement rejection as an excuse to put his full leg into the four-square ball. Four-square balls totally outrank tether balls.

To this day, I cannot say whether anyone ever did retrieve that four-square ball. Just as the ball had crested and fallen back toward earth, and careened off Teri Adam’s roof into her backyard, the large, round, red metal school bell with the white bolt in the center that mounted it to the exterior of the school’s red brick wall, clanged for ten seconds, signaling that it was time to go back into school for the next period.

That four-square ball may still be hidden amidst gladiolas and black-eyed Susans, and no doubt has lost quite a bit of its air by now.

Sometimes in elementary school, it seemed like each year in the spring, Greg Jones showed up to school with a yellow, runny sore on his lip. It looked bad. I turned my head. I didn’t want to look at it. Nobody wanted to look at it. I thought he should go see Nurse Betty just off the principal’s office, and then he did. Nurse Betty had a room there where they could hide him.

The thing would crust over every year and turn into a big red scab. Nurse Betty would treat it in the mornings with a cotton swab dripping fancy ointment that took its time doing the healing.

Greg wasn’t the smallest kid, but he was the 2nd smallest kid. Tommy Barber was the smallest kid. He used to run around the playground by himself during recess, chirping ‘beep, beep’ with his arms behind him like they were Superman’s cape. Tommy Barber grew up to become the head of the Chess Club in high school. From ‘beep beep’ Tommy in elementary school to Chess Club president in high school. No one predicted it. You wouldn’t have, either.

The chunky peanut butter and grape jelly Wonder Bread sandwich also came with a short, wrinkled-up gerbil pickle. It didn’t matter which sandwich you chose, the baloney or the pbj, you couldn’t avoid getting the gerbil pickle.

You could try to maneuver around eating the pickle by stuffing it into your milk carton at the end of lunch. But the lunch monitor ladies had this all figured out and would open the milk carton prior to a kid throwing it into the trash can. Or they’d sometimes fish it out of the trashcan. They were like army sergeants. We called them army sergeants amongst ourselves, but we didn’t really know what a sergeant even did other than order people around and be mean.

I never voluntarily ate the little green gerbil pickle. Frisell didn’t eat it. None of my other friends, either. I don’t think anybody that I knew in our entire grade ever ate one of those little green gerbil pickles voluntarily or at least with any eagerness. Including Willard. He perpetually passed over the green gerbil pickles, and he’d eat anything.

I watched Willard eat a worm once. Just once. And it wasn’t a dare. And it wasn’t a double dare, neither. And it wasn’t on a triple-dog dare… the strongest of all dares, as we learned from the movie. He didn’t even get sick. I, on the other hand, wouldn’t even touch a worm, but Big Bob Willard ate one.

Not the whole thing. I didn’t mean to imply that he ate an entire worm, chomping away, and chewing and chewing. No. He just bit the head off, or maybe it was the tail. We hadn’t had biology. We were only ten. We had science but hadn’t been taught a thing about worms.

Maybe Big Bob ate more than one small bite of the worm, but I never saw it if he did. I think he was only dumb enough to eat a worm head, or a worm tail, that one time. When we got older when we’d talk about that worm, he’d say he was ‘brave’, and I’d say he was ‘dumb’.

The brave-dumb exchange lasted for the rest of our lives. Another sixty years for Big Bob. But he knew that I knew that he wasn’t dumb; he just wasn’t studious. For clarity, and to remove doubt, let me just say it straight with no hs (now commonly called ‘bs’): Bob Willard was not dumb. But he did bite off and eat a worm head, or a worm tail. You can judge for yourself if Big Bob was brave or dumb.

So, both Wonder Bread sandwich selections came with the little, sour, wrinkled-up, pathetic juiceless gerbil pickle. Thankfully, both sandwiches also came with those tasty shoestring potatoes. To top it off, both sandwiches also came with either a decent-sized peanut butter cookie with stretch marks made from peanut butter cookie forks, or… if you were allergic to peanut butter, the cafeteria ladies would reach behind and fetch an oatmeal cookie and give it to you with a scowl. They didn’t seem to like to fetch. Dogs like to fetch more than the volunteer lunchroom ladies.

It didn’t matter which sandwich you pointed to when you slid your tray along the three stainless-steel sliding rails. When you were at the front of the lunch line, you were given the peanut butter cookie or the oatmeal cookie. One kid tried to refuse the cookie, but they didn’t allow it. ‘My mom told me not to eat the cookie.’ But they made him take the peanut butter cookie and told him to just throw it away. You weren’t allowed to say, ‘No’.

Cookie trades weren’t allowed, either. If you wanted to trade for oatmeal, you couldn’t, which suited me, because I never liked oatmeal cookies. Still don’t. Better than raison, I guess. But I didn’t like oatmeal cookies.

Overall, however, the oatmeal cookies weren’t as bad as the gerbil pickles. But oatmeal cookies weren’t near the top of the cookie class.

The school rarely offered chocolate chip cookies. Marshmallow cookies? Out of the question. Now, if we could get marshmallow cookies and strawberry jam approved in 6th grade… hmmm. Where’s Linda? Is she that good?

I was a bit jammered trying to figure out what to do with the green gerbil pickle laying limp on my lunch plate, knowing that if I tried to hide it in my milk carton it would get found by the lunch lady army sergeant doing the lunch food remnant monitoring. So I stuffed it into my front pocket, planning to throw it away in the trash can by the door on my way out. Or even throw it into the trash can of my next class. Or run outside and throw it in the big metal dented trash bin on the playground.

I was too excited to finish eating my sandwich after swallowing the final bolus of my peanut butter cookie. But then there was a big crash of plates in the back and the lunch army sergeant lady got distracted and that’s when I quickly fished the green gerbil pickle out of my pants pocket and tossed it in the trash can about twenty feet away.

All the kids in the cafeteria saw it flying across the room. It looked like the green pickle flew in slow motion and Frisell and Big Bob Willard both said ‘Great shot’ as it sailed into the can.

Then Frisell and I got up from our cafeteria seats and headed through the doors to run up the stairs for our three remaining classes, and later, to the third floor for the last fifteen minutes in our homeroom before summer and freedom. Peanut butter cookie crumb remnants jumped off the front of my buttoned shirt and blue Levi’s with a copper zipper that didn’t always stay up, as we doubled up the stairs. And then…

Kaboom! There was a thunderous clamor and it started to rain. We had not even run up two flights of the rubber-edged protective stairs before the storm ensued. All of us kids had been raised growing up hearing over and over and over:

‘If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes.’

In some parts of Denver, they’d say, ‘Wait ten minutes’. I’d heard both. We were solidly ‘a five minutes’ neighborhood. In our neighborhood, the weather could change twice if given ten minutes. But in short order, the rain stopped and we were just excited that tomorrow would be the last day of the school year when we would be let out. ‘Freed at last’ is what Big Bob called it, not expected back until the start of 6th grade. I must remember to let Linda Hart know about the cafeteria marshmallow cookie brainstorm!

It’s tough to pick a favorite summer growing up. They’re all great when you’re a kid. But the summer between 5th grade and 6th grade bubbles to the top of the list. The days were softball and basketball, and tetherball and alley hunting to rummage through over-filled garbage cans and inside open garages.

One day there was an unopened package of joke cards in Margie Samuelson’s trash can. She was a floozy, had no kids and no husband. She lived in her mom’s old-person smelly house with her smelly mom. The house was just three houses down from my house, same side of the street. Same alley. Same trash pickup. Same milkman, before he lost his job and they cancelled his milkman delivery route.

The joke card package was brand new. The first card I pulled out after stripping off the protective cellophane said:

You have a peach of a complexion — Fuzzy

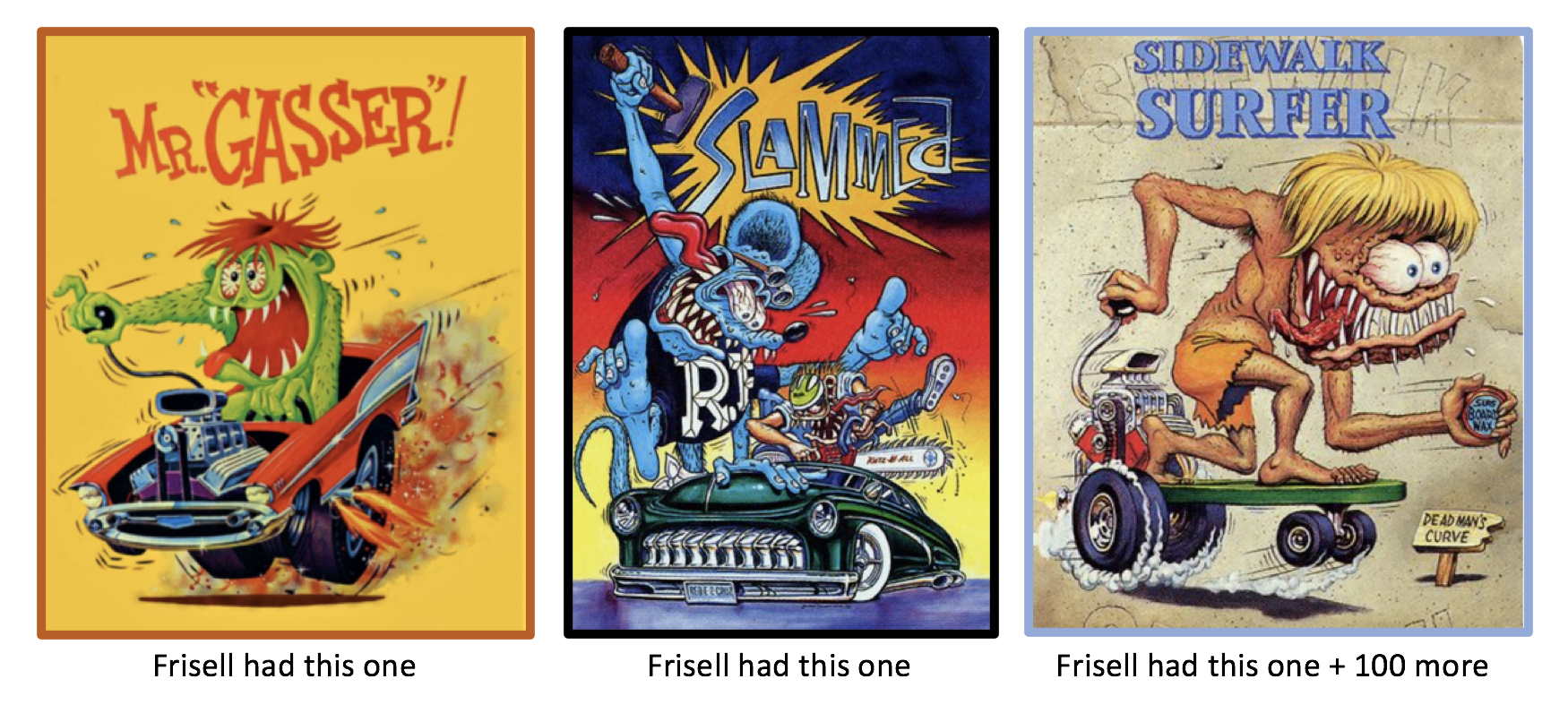

Which I thought was really clever, and it learned me how to form a joke with a circular surprise, but more impactful was that joke card had an art style that mimicked the Ed Big Daddy Roth crazy cars that many kids were really excited about. The cards were collectibles. But didn’t come with gum. That I can remember. But nonetheless, those cards were definitely a ‘thing’ for many. Not so much for me. Frisell loved those Ed Big Daddy Roth car card collectibles.

I just never really cared about cars. Although years later I’ll admit that when I got off the #13 bus stop at 9th and Madison Street, and walked up 9th Avenue toward my house, one block over to Cook Street, and saw a black 1962 Lincoln Continental with suicide side doors parked on the side of our house, I was thrilled. My dad had bought this low mileage black beauty through auction. It was the only used car he ever bought.

Tim Crow remembers the car vividly and couldn’t believe its power. Denny Blum remembers the car as the one that he and I took to get washed, in December in 1967, in the late afternoon, just prior to attending East High School’s Junior Prom. We washed the car with a long wand at a do-it-yourself car wash. Because it was a really cold night, below freezing kind of cold night, ice formed right away on the car’s exterior from the water spraying out of the wand. It made it a challenge to even put the key into the door lock. Blum had a butane lighter in his pocket. He usually had a butane lighter to enflame Sterno at his parent’s Jewish deli when asked. He used it to warm the key, and after burning his fingers, managed to melt some ice and open the door.

I was shocked, thrilled and in utter disbelief to be escorting Junior Prom Queen candidate, Carol Cantrell, to the Junior Prom. Below is a high school photograph of beautiful Carol Cantrell, the girl that should have won the Junior Prom Queen title. I voted for her. We were allowed one vote, but I voted for Carol two or three times. Other kids were doing it. Linda Hart was also a Junior Prom Queen candidate, but she didn’t win either.

The Junior Prom Queen candidates asked the boys who they wanted to escort them to the prom… and Carol asked me. We were in her black VW bug. She asked me while dropping me off at home after school. It was the first time I’d ever been in a car with her. The whole thing blew my mind. I thought she was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen.

She and I went to see the movie The Graduate at The Orpheum movie theater and when Katherine Ross appeared on screen, she was gorgeous. Carol was more gorgeous.

It was a long drive to pick Carol Cantrell up at her house on 32nd and Oneida Street on the night of the prom; almost all the way to Stapleton Airport. It was the most pleasurable and nerve-wracking drive of my life.

The theme of the prom was Alice in Wonderland. Blum’s date? Not known. And not even remembered by Blum. Which is tough to believe. He and I double-dated, meaning I drove him and his date to the prom, along with Carol Cantrell, of course.

Big Bob went separately in his own car and took Mary Selmser to the Junior Prom. She wore bobby socks which offended no one except Big Bob. He announced to everyone that his date was wearing bobby socks to the Junior Prom.

Frisell didn’t go to the prom at all. Fear of dancing. Fear of girls. Just like the rest of us. It was a common affliction. We all had it. Frisell just had it a little worse. He stayed home and started playing a guitar.

Tim Crow took his knock-out cousin, Zenta Crow. I always wished I had a cousin as pretty as Zenta. Well, I did have a cousin as pretty but she lived in San Diego. Both my cousin and Tim’s cousin, Zenta, were always tan. Healthy. Zenta was Tim’s Uncle Forrest’s daughter, and Uncle Forrest was a berating Army Drill Sergeant, disguised as Tim’s uncle. Thick military blood coagulated when he cut himself shaving, or carving, or whittling. He could have been the leader of the lunchroom lady army sergeants.

We’d drink Duffy’s Cream Soda or Black Cherry or Gabby Grape pretty much whenever we wanted when our moms didn’t know, and we chewed Big Hunk candy bars cloaked by the maroon wrapper with the large silver type. It could take fifteen minutes to eat a Big Hunk. We climbed trees and sharpened our aim with pea shooters. George Kawamoto had the best eye. Or he had the best pea shooter. Or both. Every kid had an Imperial Duncan Yo-Yo. Some of the yo-yos lit-up. If you wanted to be any good, you needed special strings to really ‘Walk the Dog’ or go ‘Around the World’ or ‘Skin the Cat’. I was not the best yo-yo yo-yo-er, but the thing fit the palm of my right hand like it belonged there. You’d attach the string to your index finger at first until some older kid would tell you to use your middle finger. That made a noticeable difference. Better balance.

I had half a dozen yo-yos at the same time at one point. It was like I was a yo-yo collector. The neighborhood was filled with them. Not as many as baseballs though, for which there were too many to count. But there were a lot of yo-yos. Frisell kept all of his yo-yo’s in his undershirts drawer, where he also hid a small pocketknife. Frisell wore sleeveless undershirts as a kid just like old people. Not all the time. Me? Never owned a single sleeveless undershirt. I’d feel like a dork, which used to be pejorative. Not now. Times change. But back then when a dork was a dork, that’s what I would have felt like if I had worn a sleeveless undershirt.

Bog-Bob ‘Worm-Eater’ Willard had a larger pocketknife than Frisell’s pocketknife. Big Bob, Frisell, and I played mumblety-peg a lot that summer. Mumblety-peg was the lawn game where two kids faced each other and took turns ‘sticking’ the pocketknife end over end into the ground, and when it stuck, the other kid would have to stretch one of his legs and foot to the knife, leaving his other foot where it was. No dragging allowed. Then, that kid takes his turn trying to stick the knife in the ground. And if he does, the first kid has to stretch one of his legs to the knife. For both kids, the foot that they left behind as the ‘anchor’ foot could never move on any of the subsequent moves. You keep playing until one of the kids can’t stretch any farther and gives up, or falls over. We were pretty sure that we were developing important skills, sticking the blade into the ground. It was intended to be another important skill, like pea shooting. If a kid could develop these skills at that young age, that kid felt like he’d gained an advantage over all the other kids. None of us really understood what parents did at work, but if it ever involved sticking knives in the ground, or spreading their legs, or pea shooting, we were preparing ourselves for successful future careers. And we were happy about that.

About a month into the summer, late one morning, after the mourning doves stopped their coo and had flown away from their telephone wire perches, Frisell and I decided to try to make money but we didn’t really know much about how to do that. We knew about lemonade stands. In fact, we had one once… maybe only a half hour, if that. After setting up, Mike Collins, a big kid from across the street, threw a basketball and knocked the whole lemonade stand over. So Frisell and I were done with that. We didn’t sell one glass of lemonade. Mike said it was an accident, and he did have a reputation for having bad aim, so we weren’t upset or anything, and he was years older than either me and Frisell. That contributed to our not being too upset.

To follow through with our plan to make money, Frisell and I decided that we’d buy big flats of brownies at Miller’s Supermarket on 7th and Colorado Blvd and then sell the brownies at a profit to the neighborhood kids from the open doors of my garage. We’d set up a table and take a couple chairs from inside the house, and also make a sign. Frisell was a great sign maker. He had a good penmanship, and was a real good artist. He should have developed his art skills, but he went a different direction, as a guitar player. It’s okay. It worked out for him.

But he could have been an artist. He painted one of the best dinosaurs on the long, paper Jurassic mural that lined the entire length of the second-floor hallway in our elementary school. The whole grade participated. I painted the worst dinosaur on the entire landscape. Kids pointing at my part of the mural would ask me, ‘What’s that supposed to be?’ That’s what they would say. Really! ‘What’s that supposed to be?’, with emphasis on the word, that. And I’d say it’s a brontosaurus, and they’d say ‘Brontosauruses don’t look like that. That looks like a scrawny chicken.’ And they were right. So Frisell had the job of making our Brownie Sale sign. I had no artistic input creating the sign, other than what it said. The lettering was all Frisell. Looked real professional. He really coulda been an artist.

Miller’s Supermarket on 7th Avenue and Colorado Blvd was nine blocks from where both Frisell and I lived. Not close for ten-year old kids, but within range. We had Stingray bicycles. Low banana seat bikes with high handlebars that could get us there and back pretty fast. But I didn’t trust carrying a sheet of brownies on my Stingray without dumping them onto the street, and the same must have been true for Frisell because we walked to Miller’s Supermarket, leaving our Stingrays in my backyard, leaning left on their kickstands. I THINK my Stingray was blue and Frisell’s was also blue, but I don’t remember, and the color of our Stingrays isn’t critical.

There weren’t many people in the Miller’s Supermarket store when we got there, and we hurried over to the bakery section on the right-hand side. There were stacks of brownie trays. Each had 24 brownie squares. We only had money for one tray, or maybe a little more than that, but not enough for two. So we examined a few trays with our eyes steady and bought the one that had more frosting than the other ones. Even though we were going to sell most of them to the neighborhood kids, we wanted the tray with the most frosting. Our customers came first and we were intent on making the neighborhood kids happy… and earn spending cash along the way, to buy more brownies to make the kids happy again and earn more spending cash. Frisell and I had discussed it and planned it out for like five minutes, which was long enough to make the business decision, so it was iron clad.

When we went to Miller’s Supermarket, we walked along 9th Avenue to Colorado Blvd, and turned right and bought the tray of brownies. When we returned to my house, we headed back along 8th Avenue, and that seemed longer because we had never walked along 8th Avenue before, so we weren’t familiar with any of the houses or yards or where the sidewalk was uneven. First I carried the brownies. Then Frisell carried the brownies. It went like that a block at a time.

8th Avenue was a busy through-street with no stop signs. Cars raced by, making it seem like we were walking really slowly. I didn’t like walking along 8th Avenue and never went that way again. Frisell didn’t like walking along 8th Avenue, neither.

On our return, at 8th and Cook Street we turned right, walked by Frisell’s house half-way down the block on the right, and continued to my house, five houses farther down on the kitty corner.

The garage doors at my parent’s house were the worst garage doors any kid had to grow up with. Two big, unevenly painted doors that opened out toward the street and didn’t stay open unless there was a box put in front of them filled with heavy stuff like tons of bolts or tools or big hunks of wood.

One of the garage doors slumped a bit. Its hinge was bent due to the excessive weight.

Frisell and I dragged a couple heavy boxes out of the garage and along the sidewalk to keep the garage doors open, and had already put the table and Frisell’s Brownie Sale sign in place. It didn’t take long before we were Open for Business.

We were just kids and didn’t know all the laws of conducting business, if there were any. We also knew we weren’t supposed to throw snowballs at busses. But those laws never stopped us.

We had heard there were rules about jaywalking. We knew they were kinda bogus. Jaywalking was a joke and every kid on Cook Street jaywalked every day. Even parents seemed to figure out that it was a dumb law.

Cops could stop you over it though, and I know that happened to Tim Crow once. It did scare him and made him straighten up like he’d just took a big whiff off of a Knorr Chicken Bouillon cube. Those are nature’s smelling salts. But they aren’t branded as smelling salts. People wouldn’t want to cook with that.

But I don’t think Tim cared one cow pie about being stopped by that policeman a couple days later. Old cow pies are like lighter fluid for campfires. The dryer the better. You wouldn’t want to pick up a wet cow pie. Well, I wouldn’t want to, and didn’t. I never picked up a wet cow pie. That’s a bumper sticker candidate right there.

Both Frisell and I would hammer busses with snowballs every opportunity we had. If you were ready, you could throw three snowballs at a moving bus before it moved past you far enough that you couldn’t hit it anymore. Sometimes you could get off four snowballs. And we didn’t hide anywhere. We’d just drop our clarinet cases in the snow or slush and start making snowballs. The bus driver wasn’t going to stop the bus.

Maybe he would if we killed somebody. And we had pretty good arms, so looking back, that was possible. But it never happened. Not that I know of. Frisell might have heard something, but I never did. He’s not here right now, so I can’t ask him about it. But if the bus driver did stop the bus, we’d just run. No bus driver was going to catch us, leaving his bus on the street in the snow. Somebody might steal it, drive it and bounce it off the sides of parked cars or hit a tree. Or some passengers might just get on-board and not pay while the driver was trying to figure out what houses we ran between, huffing and puffing, and by then we would have scooted over the backyard fence, if the gate wasn’t open, to get to the alley. And if we needed to, we’d continue up or down the alley before hopping over another fence between two more houses. There just wasn’t any way we were going to get caught.

Every kid threw snowballs at the busses. The #13 Bus Line went down Madison Street, just one block over from Cook Street, and it was on our way to school. It was on the way to Teller Elementary School as well as on the way to Gove Junior High School. To get to Teller Elementary we’d walk down Madison Street in the winter when there was snow on the ground, wait for the #13 bus and then nail it, and then turn right on 11th Avenue for two blocks to get to school.

We started throwing snowballs at busses in a serious manner in 4th grade and continued the challenge thru 7th grade. It seemed like we could get in major trouble at that point. We could throw real hard by then. That’s about three and a half years of pounding the #13 bus. I think the bus driver liked it. I really do.

You couldn’t start a day at school any better than nailing the #13 bus with a direct hit with one or two snowballs. And then after school, we’d walk home along 12th Avenue, and then turn left up Madison Street again after buying candy in the pharmacy on the corner.

The 12th and Madison Street corner pharmacy was a kid’s mecca. It had a marble soda fountain where you sat on the round high red vinyl stools that swiveled at the counter. The older kid with red spots on his face made the soda fountain drinks in tall glasses with straws that could bend down at the end to reach our lips. He wore a paper pointed hat and was called a Soda Jerk, which didn’t sound too good as a title to me since it had the word ‘jerk’ in it. The pharmacy also had small, pocket-size squirt guns in the summer and sometimes they had sling shots, but it also had a huge candy display behind glass that was higher than the soda fountain.

Sometimes during the year they had those big red wax lips that weren’t candy, and pretty much were terrible, that made you feel like an idiot when you bought them. Frisell bought one once and ditched it into the metal trash can about two minutes later. The pharmacy/candy store also sold those little paraffin ‘coke’ bottles filled with about a tablespoon of some liquid… but they had tons of great candy; lots of which only cost a penny or two. They had candy bars, too, but you needed a nickel and they didn’t seem worth it. For some of the real big new candy bars, they were asking for a dime. If I was going to spend 20 cents on candy on the way home from school, why would I buy the bigger candy bars instead of 10 penny candies and a Duffy’s pop? Except the Duffy’s pop was tougher to carry which was a factor. And when they had Big Hunks, I’d buy those. Same with Bit-O-Honey. If I had remembered Bit-O-Honey earlier when writing this, I would have included them before now.

But the point is that when walking home from Elementary School, we traveled three blocks up Madison Street to get to 9th Avenue, rather than just the two blocks we walked down Madison Street to go to school in the morning. And we took advantage of the extra block to pound the #13 busses going either direction on Madison Street. Plus, the snow was better for making snowballs in the afternoon because the sun had warmed the snow up just enough so the snow would stick together and make a real good throwing snowball. There was no question that the snow was better for making snowballs on the way home from school than it was on the way to school. And there was no better way to end the school day than pounding the #13 bus with a barrage of snowballs, even if the Duffy’s tipped over and colored the snow red or purple. I felt sorry for the kids that didn’t have a bus line on their way to school. Like Steve Irwin. He lived right across the street from Elementary School. It was everything to Frisell and me.

The brownie sign Frisell made said:

BROWNIES

ONE FOR A DIME

TWO FOR A QUARTER

Maybe some of the dumb kids in the neighborhood would go for two. It wasn’t up to us to make sure all the kids in the neighborhood could add numbers or knew their times tables. Most of the kids wouldn’t have an honest way to have a quarter anyway.

Brownie sales were good right away and the word spread quickly that we had a big business going. George Kawamoto came right over and Francine Hoag did, too. Bea Davis bought one, and Denny Blum bicycled by to ask if they were kosher. Blum’s parents had a kosher catering business and they kept kosher at home, but we didn’t know much about it. I know that I ate a lot of bagels and lox at Denny’s house, so I know those were kosher, but I didn’t remember eating many brownies over there. So Frisell and I didn’t know if the brownies were kosher, so we told Blum that we didn’t know. Denny hung around a while to see how this was going and ate a brownie or two, himself, but left after only about fifteen minutes.

A few of the Collins’ kids checked it out, too. They lived kitty corner from me, right across the street, but I didn’t know any of them at all. I think they went to the Catholic School up the other direction from our elementary school. But there were about a hundred of them Collins’. One was named Mike. He was the one that threw the basketball that accidentally broke up the lemonade stand that Frisell and I had a year earlier. Mike Collins was older than us. He was even older than my brother’s age. And there was another Collins’ kid, a girl named Pam, and there was one named Judy, (not that Judy Collins, but that Judy Collins did go to our high school, but she was twelve years older than we were, and still is if my math is straight). I think there were three Collins’ kids named Ricky. There were tons of Collins’ kids.

Nobody was buying brownies two for a quarter. We did have plenty of two-brownie sales to plenty of our happy customers. But they always paid with two dimes or four nickels or some combination that sometimes included pennies. But then, during a quiet time, another one of the runny-nosed Collins’ kids came over. Another younger brother. He walked right up to us and smacked a real shiny quarter down onto the center of the brownie sales table.

‘I want to buy two brownies, please.’

It was our first quarter sale! A potential big moment. Frisell checked out the quarter to make sure it was real.

Once the quarter passed Frisell’s bite, we looked at each other and couldn’t believe it. We were happy and the neighborhood kid seemed happy, and we sold out, left the garage and the table and sign outside the garage, held the change firm in our pockets, and returned to the Miller’s Supermarket on 7th and Colorado Blvd to buy more sheets of brownies. On the way, we decided that we would buy some candy bars, too. It wasn’t too early to expand our business. Maybe we wouldn’t even need to go to school next year.

When we returned to my house after buying the brownie trays and the candy bars, it was obvious something was wrong. The little Collins’ kid that bought the two brownies with the shiny quarter was there, in front of my parent’s lousy garage, in front of our make-shift brownie table stand, and he was crying real hard. One of his older brother’s was there, too, and so was his mom.

Neither his mom nor his older brother, Kendall, were crying, but you could tell that his mom was upset and that Kendall was upset, too, even though it looked like he had a smirky smile. They were just standing next to the table and the sign that Frisell had made, waiting for us to return. The mother was smoking a cigarette. I figured that I figured out what the problem was in advance of being yelled at, so I figured we’d just give them a couple brownies for free and fix it. They probably thought that we had cheated the little Collins’ kid out of a nickel.

‘Did you sell brownies to Jimmy earlier?’ Mrs. Collins opened, pointing directly at Frisell’s sign.

‘I think so,’ I responded cautiously.

‘And did he give you a shiny quarter to buy them?’

‘Uh-huh. I think so.’ Frisell nodded his head in agreement.

‘Did you know that he took that shiny quarter from his father’s hidden coin collection from the back of our bedroom closet and that that shiny quarter was a mint condition 1935 S?’

‘Not really. I didn’t know.’ I was just being honest. This seemed like one of those times that the less I said, the better. Plus, I didn’t really understand what she was talking about.

‘Can you give me that 1935 S shiny quarter back, before Jimmie’s father gets home? That collector’s quarter cost Jimmie’s father thirty-five dollars.’ Mrs. Collins’ face was turning Red Delicious apple red.

‘I don’t think so.’ I looked at Frisell and he just shrugged. Our new brownies were starting to melt, and so were some of the chocolate candy bars that we stuffed into our pockets. We had no idea what she was talking about a quarter costing thirty-five dollars.

‘Why not?’ she angered.

‘We spent it up at the supermarket buying more brownies. We got some candy bars, too. You can have some for free. Honest. Here, take two for free.’

Mrs. Collins stormed around the lilac bushes and headed over to the back door of my house, only forty feet from where we were standing, and banged on the screen door pretty hard.

My mom answered the screen door and Mrs. Collins stood there talking to my mom in a loud voice, and I didn’t hear my mom saying too much back, and Jimmy started crying more while this was going on. Jimmy’s older brother, Kendall, stayed with Frisell and me at the garage while the conversation was going on between my mom and his mom, and while he was staying there with me and Frisell, while his mom was complaining to my mom, he examined the new tray of brownies and the candy bars Frisell and I had brought back from Miller’s Supermarket.

‘How much for one chocolate brownie and a Snickers?’

‘That’s the same as getting two brownies, so it’s 25¢.’

Kendall Collins reached in his pocket, and then gave Frisell and me an old quarter, and he got one chocolate brownie and one Snickers. Frisell and I just looked at each other, raising our eyebrows, and threw our hands up in the air. Seems like Kendall wasn’t too bright. Maybe they didn’t teach math in Catholic school. That would be cool.

Turns out we didn’t get in any trouble for selling the brownies at two for a quarter. It just passed right by Mrs. Collins. And Kendall didn’t know. And we already know that Jimmie didn’t know. And yet, Mrs. Collins had been standing right by the sign the whole time she was upset while yelling at me and Frisell, and she even pointed right at it.

She only cared about the quarter that her husband had paid thirty-five dollars to buy. She didn’t even realize that we’d scammed little Jimmy… and now his older brother, Kendall.

Brownies for Sale

One for a Dime, Two for a Quarter

Both Frisell and I realized that we had dodged a bullet with that sign. We tore it up into little pieces and threw the pieces into the incinerator next to the alley. Frisell made a new sign because now we had candy to sell, too. The new sign advertised:

Brownies and Candy Bars

FOR SALE

25¢ for Two

We didn’t know much about business, but we knew quarters were more valuable than dimes.

Neither one of us had ever heard of a dime being worth thirty-five dollars.

I can see this happening! I like this story.

LikeLike